Darkness engulfed the Arizona desert as the first of two aircraft closed in on the landing zone. The mission, part of the Marine Corps’ controversial evaluation of the MV-22B Osprey, called for a simulated communication blackout.

Lt. Col. Jim Schafer, who was co-piloting one of two other Ospreys that were trailing the first pair, sensed a problem as he watched their descent. “These guys are too high,” he said aloud. His decision to maintain radio silence has haunted him for the last 16 years.

It was April 8, 2000, and seconds later, that Osprey lost lift, flipped and plummeted to the ground. All 19 Marines were killed, marking one of the deadliest test flights in U.S. military history. The second Osprey encountered its own trouble, slamming to the ground and skidding 100 yards before coming to a stop. Miraculously, no one in that aircraft was seriously hurt. The Marine Corps would blame the pilots, Lt. Col. John Brow and Maj. Brooks Gruber, for causing the deadly crash, refusing to back down from that conclusion even after a formal investigation cleared Brow and Gruber of wrongdoing.

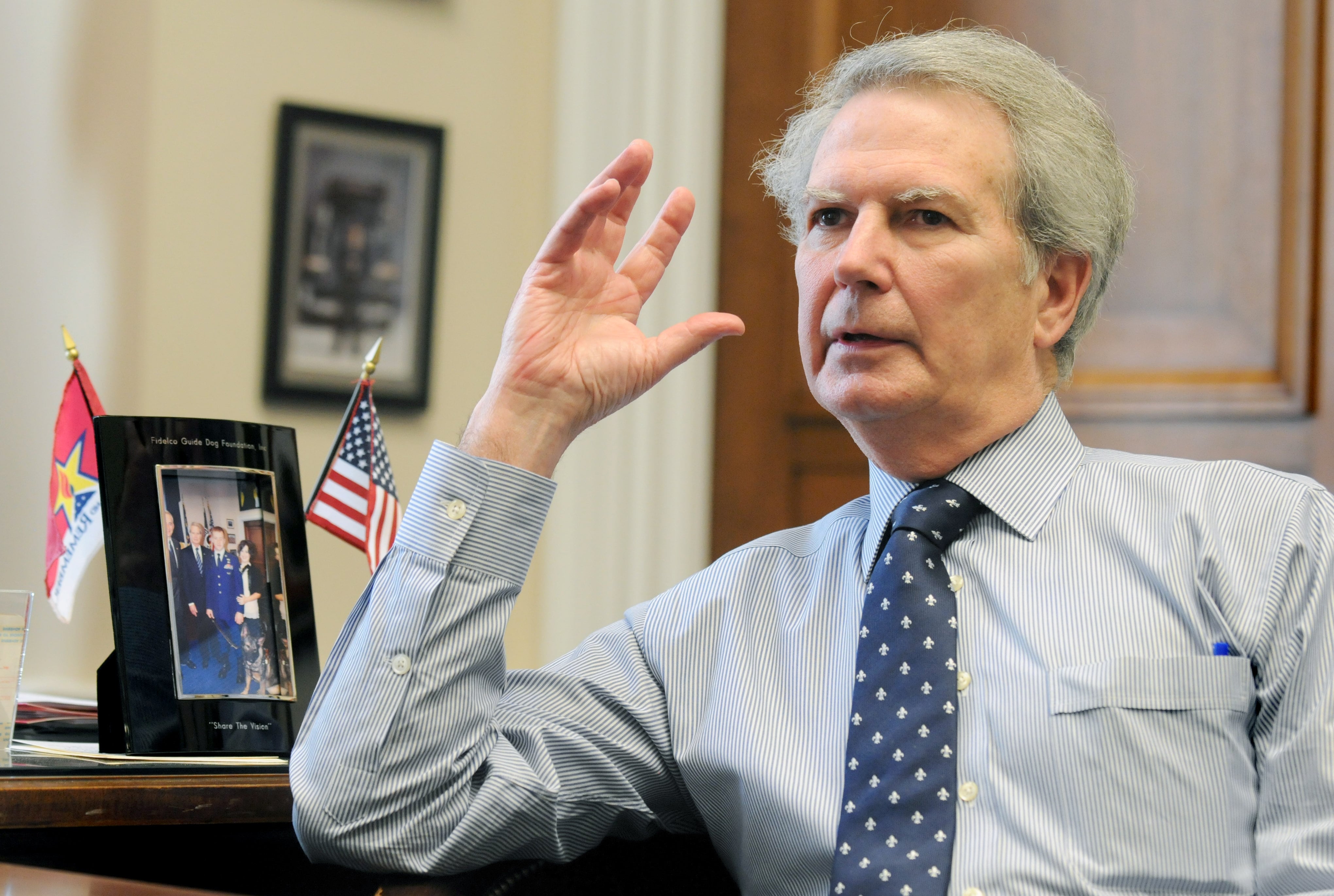

It’s a well-known story, in large part because one congressman, Rep. Walter Jones of North Carolina, waged a relentless battle to clear the pilots’ names. As the years went by, his effort seemed to become more futile. The service’s senior-most leaders appeared uninterested at best in the congressman’s argument, Jones told Marine Corps Times — heartlessly dismissive at worst.

This spring, the Defense Department intervened, issuing a letter to Jones and the pilots’ families formally absolving Brow and Gruber and gently rebuking the Marine Corps for its obstinance. For Jones, whose persistence came to irritate Marine Corps headquarters, the decision marks an important moral victory — right overcoming wrong. For the pilots’ widows, it brings the closure they’ve so desperately sought since burying their husbands.

For Schafer, who says he suffers from survivor’s guilt, the resolution represents far more. Marines never leave their brothers and sisters behind, he said. Everyone who participated in the Osprey’s development — the ground crews, the pilots and the generals orchestrating it all — faced immense pressure to meet benchmarks and deadlines. Failure was not an option, even if it meant fudging the truth. Brow and Gruber were victims, he said, of an overly aggressive effort to field this aircraft before all of its many engineering problems were fully resolved. Blaming them for the crash was a sin, Schafer said. They deserved better.

“It took us 16 years to bring our guys off the battlefield,” he said. “We left them there, and we finally brought them home with honor. That survivor’s guilt that I live with — that I didn’t call on them to wave off, that I didn’t want to break radio silence — well, that letter helps me.”

Brow and Gruber joined the Multi-Service Operational Test Team almost a decade before the MV-22 reached initial operational capability, a phrase the military uses upon declaring new aircraft and vehicles safe and fit for duty. Being a part of this team was an honor, said Connie Gruber, Brooks Gruber’s widow. “He believed in its mission,” she said.

Schafer, who’d already been with the team for a couple of years, wrote the Osprey’s training plan for pilots learning to fly the aircraft. Everyone on the test team, he said, shared that sentiment. “We wanted to be the guys doing it. When we walked into a room,” he recalled, “people would say, ‘There’s one of those V-22 guys.’”

Over time, though, Schafer said the test team felt pressured to meet unrealistic deadlines. The Osprey acquisition program was deemed vital by the Marine Corps, whose "medium lift" helicopter fleet — comprising the venerable Vietnam-era CH-46 Sea Knight — was wearing out. The service's leaders bet big — real big — on the Osprey. Its projected initial cost of $30 billion came saddled with enormous scrutiny from Congress. The test pilots felt obligated to deliver favorable feedback, Schafer said. They weren't allowed to be 100 percent objective.

"On one hand," he said, "we wore a blue hat to test and evaluate it. Then we also had a green hat. We should never have had our green hat on while testing."

Connie Gruber recalled feeling like the Marine Corps had so much riding on the Osprey's success that it the machine became more important to the service's leaders than people tasked with operating it. Corners were cut routinely, she said. Skipped or inadequate testing led to hidden dangers. "The fatal factor," she added, "would be the greediness that took the program from event-driven to timeline-driven."

The demands were "almost impossible," Schafer said. For example, the night of the crash marked the first time the test team was authorized to put four Ospreys in the air. Until that point, there had been so many mechanical flaws that the Marines never even had that many up and running at one time.

"It was so obvious that we were pushing an aircraft that had no business being run through an operations evaluation," Schafer added. "We were testing an aircraft that was under-cooked. Our job was to test it ... and deliver a favorable report to the department of test and evaluation."

There were so many unknowns. The pilots weren't always certain how the aircraft would respond under certain rigors. Schafer had his own close call while switching positions with another Osprey during a nighttime formation flight. As his aircraft picked up speed, it rolled 80 degrees before the flight-control computers kicked and stabilized it, he said.

Another unknown, the one investigators ultimately determined to have caused the Arizona crash, was a phenomenon called "vortex ring state." If an Osprey descends too quickly, with enough forward speed, air can engulf the rotors and cause them to stall. No one knew how to correct the aircraft in such a dangerous state.

Brow and Gruber were among the Marine Corps' best pilots, Schafer said, yet they did not recognize the conditions that precipitated their deaths. That troubles him to this day. "There's something wrong with that," he said, embittered still by the pressures the pilots faced that led to compromised standards.

That, Schafer said, was a result of the constant compromising and under-testing the pilots on the test team were forced to deal with. In addition to testing the Osprey that night in Arizona, Schafer said Gruber and Brow were also flying as Weapons and Tactics Instructor students, which was why it was a no-communication event.

"I should've waved them off," Schafer said. "I should've said, 'Hey guys, stop.' I should've put my blue hat on as operational test director, said 'I work for the Navy right now — we're testing an aircraft. ... But I had my green [Marine Corps] hat on that night."

The Osprey crashed nose first and burst into flames. Schafer and his co-pilot were forced to circle the site for 45 minutes. Their orders were to ward off any media who tried to capture imagery of the scene.

"It was a horrible thing that happened that night," he said. "And where was all this pressure coming from? It's not like we were saving hostages that were about to be taken out by ISIS or something — our enemy was the pressure from the timeline."

Eight months after the Arizona crash, four more Marines were killed during a test flight in North Carolina. The Marine Corps temporarily grounded its Ospreys as a result. At that point, the program had claimed 30 lives.

The six-page letter absolving Brow and Gruber was written by Deputy Defense Secretary Robert Work, a retired Marine officer who was on active duty as the Osprey was developed. Connie Gruber took the letter to her husband’s grave site in Jacksonville, North Carolina, and laid it on the ground beside his headstone. He and Brow “can now rest in peace knowing their names exemplify the Marine Corps’ values of honor, courage and commitment,” she said.

Brow’s widow, Trish, said the letter was tough to read, forcing her to relive the nightmare. Still, the anniversary of the crash was a little easier. “The load wasn’t as heavy this year,” she said.

John and Trish Brow had two children who are now in their 20s. The Grubers’ daughter was a baby when the crash happened. Brooke, who is named for her father, is 16 years old.

The widows banded together three months after the crash, when the Marine Corps issued a news release stating “the pilots’ drive to accomplish the mission appears to have been the fatal factor.” They felt their husbands had been dishonored, and the Marine Corps, Gruber said, didn’t seem to care. “My questions and concerns,” she said, “were never fully, properly, nor seriously addressed.”

Work first began looking into the case last year, and eventually concluded the Marine Corps’ press release was inaccurate. Those words, he wrote, “were incorrectly interpreted by many to mean the actions of Lieutenant Colonel Brow and Major Gruber were solely responsible” for the crash.

“There was a lot more behind this accident,” Work told reporters after sending the letter. ”... It was impossible for me to designate the fatal factor, therefore saying that the pilots were primarily to blame, it was hard for me to do so.”

There were clear deficiencies with the Osprey’s development that were fixed after the crash, he wrote in his letter. While human factors did contribute to the crash, “it is impossible to point to a single ‘fatal factor’ that caused this crash,” he said. In fact, all of the events leading up to the crash made the April 2000 accident — or one just like it — probable or perhaps inevitable, he wrote. “I hope this letter will provide the widows of Lieutenant Colonel Brow and Major Gruber some solace after the years in which the blame for the ... accident was incorrectly interpreted or understood to be primarily attributed to their husbands,” he added.

The Marine Corps offered little in response to a question about whether the service’s public affairs organization, which oversees media relations, has implemented policy changes as a result of this case. “We never have talked about an ongoing investigation and don’t until a report is issued,” said Capt. Sarah Burns, a spokeswoman at the Pentagon. “Then we speak to what the report says.”

When Connie Gruber first approached Jones seeking help, he vowed to her the pilots’ names would be cleared during his lifetime. “Both families have hurt so badly ever since the accident, and they have been frustrated,” he said. “The lawsuits have been over for years. This was just to get a correction to the misrepresentation that the pilots alone are responsible for this.”

Jones, whose congressional district includes Camp Lejeune and the nearby Marine Corps air stations at Cherry Point and New River, has made more than 100 speeches on the House floor in defense of Brow and Gruber. All of the noise made him unpopular with the Marine Corps’ senior leadership.

“I have in my office a Voltaire quote ... specifically for this journey,” Jones said, referencing the 18th century writer and philosopher. “It says, ‘To the living, we owe respect. To the dead, we owe the truth.‘” The congressman had become convinced that some within the institution were willing to do or say anything to protect the V-22 program. He’d met with three Marine Corps commandants over the years seeking to have the case reexamined: Gen. Michael Hagee, Gen. James Conway and Gen. James Amos, who before ascending to the service’s top post was intimately involved in the Osprey’s early development.

“They never showed a whole lot of interest in it, no matter what kind of information I had gathered,” Jones said. “If they had spent a little more time looking at what I had, and been open minded about it, they would’ve come to the same conclusion. There were people around the Marine Corps who were unwilling to give these two pilots the benefit of the doubt.”

Work’s letter arrived in Jones’ office on Feb. 11. “I spent some time crafting it, guided by prayer, research and discussion with a variety of experts,” he wrote to Jones in a December draft of the letter. “I know I didn’t go quite as far as you desired, but I believe it does correct the record, and my soul is at peace.”

Jones presented the letter to Connie Gruber and Trish Brow. Both agreed it was exactly what they needed to move forward.

The letter proves that Brow and Gruber were pioneers who made “lifesaving contributions to the history of Marine Corps aviation,” Connie Gruber said. That’s true, Schafer agreed. Marines flying the Osprey today follow protocol on high rates of descent, a direct result of the crash.

The Osprey has become one of the Marine Corps’ most important aircraft. It can travel vast distances, enabling a wealth of missions across the world. Despite the challenges and tragedies involved in getting the aircraft fielded, Schafer called it a phenomenal machine. “I love it — it’s a wonderful aircraft,” he said. ”... I truly believe this aircraft is what we wanted to do and needed to do.”

Kelly Burdick, a spokeswoman for Naval Air Systems Command, said the men and women who test new aircraft allow operators and mission planners to better understand how it will perform in various conditions. “Both the strengths and limitations of the system are documented and understood, and built upon over time,” she said. “As a result of this continually increasing experience and the updates that are being introduced, the V-22 currently has one of the best safety records in the fleet.”

In addition to Gruber and Brow, those killed in the crash were: Sgt. Jose Alvarez; Pfc. Gabriel Clevenger; Pfc. Alfred Corona; Lance Cpl. Jason Duke; Lance Cpl. Jesus Gonzalez Sanchez; Lance Cpl. Seth Jones; Cpl. Kelly Keith; 2nd Lt. Clayton Kennedy; Cpl. Eric Martinez; Lance Cpl. Jorge Morin; Cpl. Adam Neely; Staff Sgt. William Nelson; Pfc. Kenneth Paddio; Pfc. George Santos; Pfc. Keoki Santos; Cpl. Can Soler; and Pvt. Adam L. Tatro.

Their role on this mission was equally important, Schafer said. When the military tests new transport aircraft, passengers ride along to provide feedback on the experience, input that further informs development. Despite the struggle to forgive himself, he knows Brow and Gruber did all they could to save those men. “Those guys were the best in the Marine Corps,” Schafer said. “I want people to know that those two Marines did the best they could.”

Pentagon Bureau Chief Andrew Tilghman, Staff Writer Matthew L. Schehl and Video Journalist Daniel Woolfolk contributed to this report. Gina Harkins is the editor of Marine Corps Times. She oversees reporting on Marine Corps leadership, personnel and operations.