More than 300 Marines have earned the Medal of Honor since award's inception in 1861. But missing from that list is perhaps the most legendary Marine, whose memory still looms large in the lore of the Corps: Lt. Gen. Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller.

The image of Puller's iconic frown and his memorable quips about combat have come to define what it means to be a Marine for generations. Puller once told his troops, when surrounded by enemy fighters in Korea: "All right, they're on our left, they're on our right, they're in front of us, they're behind us ... they can't get away this time."

Puller earned five Navy crosses, the nation's second-highest honor for valor. At least two serious attempts have been made to get one of Puller's awards upgraded to the Medal of Honor, but they failed. Even today, Marine veterans and devotees still grumbled that Puller deserves to be recognized with the nation's highest honor and the book has not been closed on the matter.

"Marines still today in boot camp chant his name. They all still do know about him and they should keep his spirit alive," said Kim Van Note, president of the Basilone Memorial Foundation, a charity named for one Marine Medal of Honor recipient who served under Puller's command at Guadalcanal, Gunnery Sgt. John Basilone.

"I definitely believe he should have been awarded the Medal of Honor," Van Note said.

The Pentagon has recently begun to acknowledged publicly for the first time that bestowing military honors and medals for valor is an imperfect bureaucratic process – critics say it can seem arbitrary.

A force-wide review of combat medals that began last year is confirming that dozens, potentially hundreds, of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans were not properly recognized for their bravery on the battlefield and will have their honors upgraded. Former Navy Secretary Ray Mabus has recommended that two Navy Cross recipients have their awards elevated to the Medal of Honor.

While the review is officially limited to the post-9/11 wars, questions persist about whether Puller and other past warriors have been appropriately recognized.

LEADERSHIP

Marine Col. Chesty Puller, right, studies the terrain in Korea before advancing.

Photo Credit: USMC Archives

Puller, a Virginia native, enlisted in the Marine Corps during World War One and attended boot camp at Parris Island. He was soon commissioned as a second lieutenant a year later, setting in motion a career that would stretch more than three decades.

Whether serving in Nicaragua, the Pacific or Korea, Puller was routinely on or near the front lines, often exposed to the same risks as his men, said retired Marine Col. Jon Hoffman, who wrote the biography "Chesty: The Story of Lieutenant General Lewis B. Puller, USMC."

"In Nicaragua in particular, he led the charges against the enemy himself rather than telling his men to charge while he held back," Hoffman told Marine Corps Times. "It is a style of leadership common across the history of warfare, but one which he continued up through a relatively high level of command."

Puller earned his first Navy Cross as a first lieutenant. Puller led several successful attacks against Nicaraguan bandits between February and August 1930, despite being outnumbered, according to his Navy Cross citation.

"By his intelligent and forceful leadership without thought of his own personal safety, by great physical exertion and by suffering many hardships, Lieutenant Puller surmounted all obstacles and dealt five successive and severe blows against organized banditry in the Republic of Nicaragua," the award citation says.

During World War II, Puller temporarily took command of a Marine battalion at the Battle of Cape Gloucester after both the battalion commander and executive officer were wounded, the citation for his third Navy Cross says.

"Lieutenant Colonel Puller unhesitatingly exposed himself to rifle, machine-gun and mortar fire from strongly entrenched Japanese positions to move from company to company in his front lines, reorganizing and maintaining a critical position along a fire-swept ridge," the citation says.

"His forceful leadership and gallant fighting spirit under the most hazardous conditions were contributing factors in the defeat of the enemy during this campaign and in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

Puller's awards primarily recognize his leadership rather than the danger he placed himself in during battles, said Hoffman. One aspect of his leadership style was putting his Marines first.

"What endeared him to his men was not just that demonstrated bravery, but also the way he bonded with them and looked out for them, in a way that many other equally brave officers of the time did not," Hoffman said.

In his book, Hoffman wrote how after one battle at Guadalcanal, Puller spent the night bucking up his Marines after an attack against Japanese troops had failed.

"A squad leader who had experienced the 'terrible feeling being under fire the first time' thought that the colonel's display of courage and calm during the fight 'really raised our morale,'" Hoffman wrote.

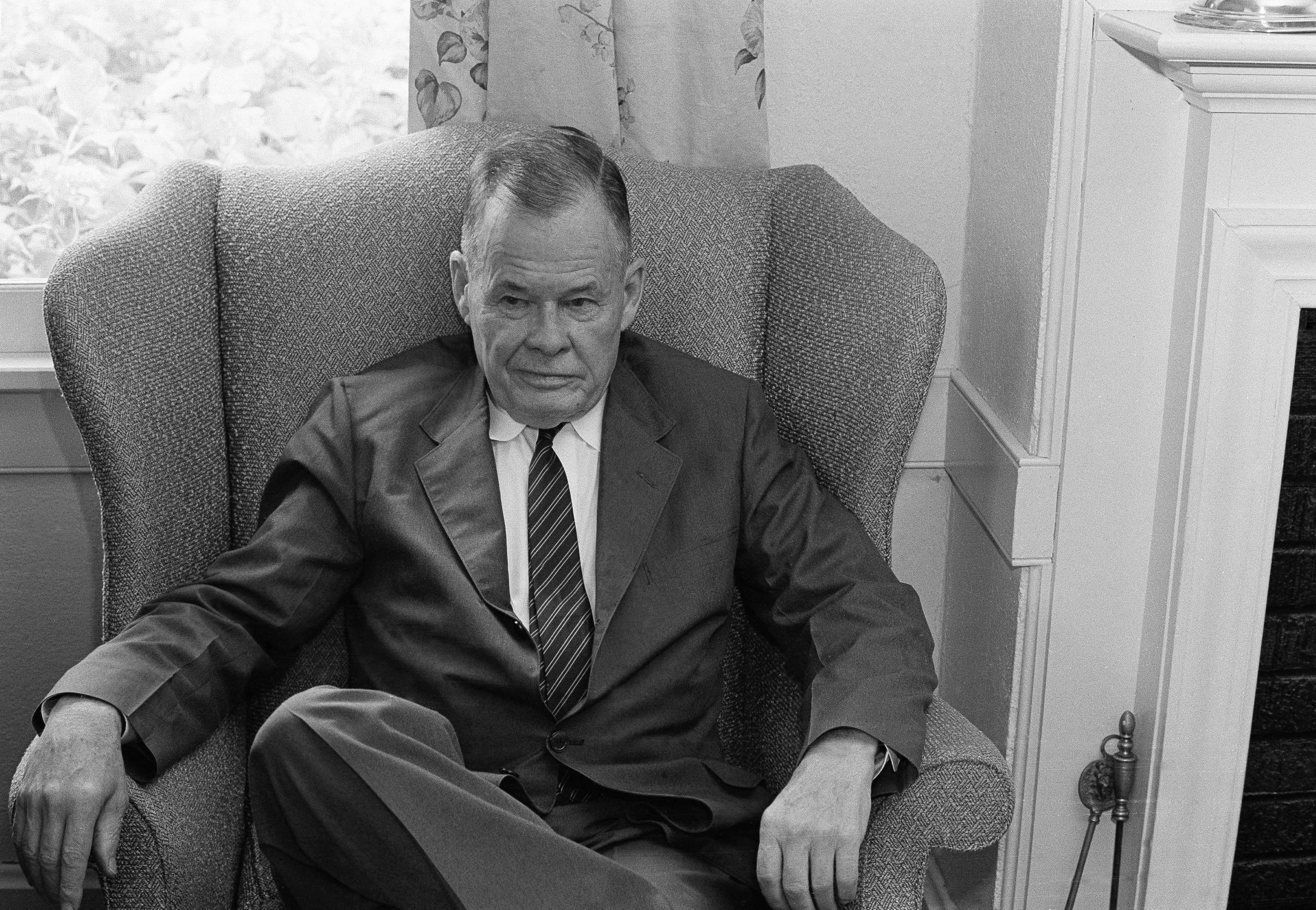

Retired Lt. Gen. Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller in an 1965 photo. (AP Photo)

INITIATIVE

As a battlefield commander, Puller did not wait for orders when things went wrong. He took initiative and responded aggressively and quickly.

One example of this is in September 1942, when Puller, on his own authority, led a mission to rescue nearly 400 Marines trapped behind enemy lines. "While others dithered, Puller acted," Hoffman said.

Puller was leading one of three units in an operation to cross the Matanikau River. The Marines only expected to encounter a few hundred enemy troops, but the Japanese had amassed roughly 4,000 in the area, Hoffman wrote.

The plan to cross the river quickly fell apart, but the 1st Marine Division ordered the attack to continue.

When a small group of Marines launched an amphibious landing behind enemy lines, they were surrounded by the Japanese and cut off from the sea. Outnumbered by Japanese troops, the unit "was on the verge of reenacting Custer's Last Stand," Hoffman wrote.

Puller was leading a battalion elsewhere on Guadalcanal. He realized that time was running out for the trapped Marines. He became enraged that his superiors had not come up with a plan to save them.

"He used his initiative to figure out what to do and then make it happen, while others were preoccupied with other issues or simply unable to come up with a solution to this difficult problem of a battalion surrounded behind enemy lines," Hoffman said.

Puller boarded the destroyer Monssen and worked with the ship's captain and gunnery officer to come up with a plan to shell the Japanese troops and allow the trapped Marines time and space to withdraw, Hoffman wrote.

The first landing craft to approach the beach where the Marines had gathered came under fire, forcing some to back off, Hoffman wrote.

Chesty Puller, pictured here as a colonel, speaks to Brig. Gen. Edward Craig in Korea.

Photo Credit: USMC Archives

"Chesty had already boarded one of the small craft," Hoffman wrote. "He ordered it into shore and shouted at others to follow him. The battalion laid down additional covering fire and the landing boats finally came in at both locations. The Marines carried their wounded out into the surf, but had to leave their dead behind."

Puller had gone far outside his normal authority, but saved many Marines who might have otherwise been killed. None of his superiors had authorized him to work with the Monssen's captain, but the skipper agreed to help rescue the Marines.

"That's what makes this operation so special in my eyes – Puller responding to the situation, figuring out what to do, and then making it happen, all in a very short space of time," Hoffman said.

"It was all about rescuing his men, when no one else seemed sufficiently concerned about them."

UPGRADE

Puller's service record shows he was never recommended for the Medal of Honor, according to the Marine Corps History Division. Still, some people have unsuccessfully campaigned for one of Puller's awards to be upgraded, including Medal of Honor recipient Col. Gregory "Pappy" Boyington.

In February 1952, Boyington wrote directly to President Truman, calling Puller "the greatest soldier of any service that has ever existed."

"I had the honor and pleasure of serving under General Puller when he was a captain in the Marine Corps," Boyington wrote. "I never served under General Puller in combat, however, I know his record from A to Z. I would like better than anything in the world to have you look into his record. General Puller is entitled to the Congressional Medal of Honor more than any living person in the United States."

But Truman may have never seen Boyington's letter, said Jim Armistead, an archives specialist at the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum.

"Much of his incoming mail was filtered and referred to other more appropriate offices," Armistead said. "For example, if a mother who wrote to President Truman wanted an early discharge for her son so he could come home to work on the farm, her request would be forwarded to the Department of the Army."

In this case, Boyington's letter was sent to Truman's naval aide, Adm. Robert Lee Dennison, Armistead said. That April, Dennison received a response from the commandant's office saying that Puller had never been recommended for the Medal of Honor, according to the History Division.

Another attempt to get President Kennedy to award Puller the Medal of Honor was referred to the Marine Corps, which determined Puller was no longer legally eligible to be considered for the nation's highest award for military valor, Hoffman wrote.

In recent years, there have not been any serious campaigns to upgrade one of Puller's awards. Hoffman said.

"Usually a service would need substantial new information (lost recommendations or witness reports, or new witness reports provided by surviving veterans)," Hoffman said. "None of that came forward in Puller's case – the people pushing for it were simply asking that his case be re-evaluated."

Chesty Puller's impact on Marine culture continues today and his image is often invoked as a symbol of the Corps ethos of grit and mettle.

TODAY'S REVIEW

The extensive review of awards was ordered a year ago by former Defense Secretary Ashton Carter amid longstanding complaints that troops who served in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere were being overlooked for the Medal of Honor.

In the past, the Defense Department has reviewed and upgraded the honors bestowed on individual service members and also for minority racial groups for example African Americans and Japanese-Americans. But the Pentagon's latest effort is the first time the military has second-guessed its judgment across the board for large span of time and sought to upgrade dozens or potentially hundreds of troops.

One element of Puller's record might discourage calls to upgrade one of his Navy Crosses. Only one other veteran received five Navy Crosses, Navy Submarine Commander Roy M. Davenport.

A decision to upgrade one of Puller's Navy Crosses would mean he no longer shares the record for most Navy Crosses and might be self-defeating in some people's eyes.

No matter whether Puller eventually receives the nation's highest military award for valor or not, there is no question that his bravery is enshrined in Marine Corps cannon, said Medal of Honor recipient Sgt. Dakota Meyer.

"I don't think that Marines are defined by the medals on their chest," Meyer told Marine Corps Times. "I think Chesty Puller – he would never walk around and define himself as a five-time Navy Cross recipient. He would define himself as a United States Marine."

By any definition, Puller is a legend, Meyer said. His legacy is not defined by which valor awards he received.

"I think this award stuff gets blown out of proportion," Meyer said. "The guy is a hero. Hell, the guy's got five Navy Crosses. One Medal of Honor isn't going to make him a better man or more of a hero in my book."