Kate Mannion spent college drinking and playing rugby, so when she joined the Marine Corps in 2008 she did so to become a better person.

She trained as a military police officer and was soon on deck for deployment. At that time the Corps needed female Marines to engage Afghan women. She still had a healthy dose of young, adrenaline-fueled ideas about life in a combat zone and “killing terrorists.”

As a young lance corporal she went into the deployment with pessimistic views about the people, the culture, what she would encounter, how she would be treated as a woman, an American, a Marine.

But her experiences there “ended up flipping me on my head,” she said.

As thousands fled Afghanistan last month, virtuous human moments arose — Marines lifting a child over barbed wire, a baby birthed on an evacuation flight, scattered networks of U.S. veterans scrambling to help their Afghan comrades reach safety.

But amid the chaos, death and destruction that rolled across the country, taking U.S. troops with it, questions emerged, “What went wrong?” “Who’s to blame?” “Was it worth it?” “What’s to come?”

The staggering cost of the 20-year war in Afghanistan, which took an estimated 171,000-174,000 lives and $2.3 trillion, according to a recent report from the Costs of War project at Brown University, hovers darkly over these questions. The war directly resulted in the deaths of 2,442 U.S. service members, according to the study, and the Defense Department reports that more than 20,000 were wounded, many of them catastrophically.

Military Times spoke with Afghanistan veterans about how they struggle to balance the scales of what was given and what was lost, to find what was gained. What will they choose to remember and how will they reconcile those memories as the years pass?

For some, their thoughts flit between worthwhile and futile. Some know they tried to help but see their good intentions as doomed all along. Others know they made a difference and their work will manifest itself in an Afghanistan that is one day free.

For this small group of veterans, the answers to these questions don’t often revolve around combat, but are rather intensely personal — the memories, the images, the discussions with Afghan individuals that they carry with them and are theirs alone.

Mannion worked on the female engagement teams, two female Marines embedded with all-male infantry units, often accompanying Navy medical units providing care.

At times, she sat with village women in a separate area while male Marines met with tribal leaders.

Talking was often like a game of charades.

“The women would turn on music, they would be dancing, they would put makeup on us, they would give us all the sugar they had in the house in our tea so the teacup would literally be like half sugar with just a little tea on top,” Mannion said.

The women drew big red circles on her cheeks and then gathered around, erupting in laughter.

“They were just howling,” she said.

She knew the women were putting themselves at risk through these small acts.

And they’d talk.

“How are you, is there any way we can help?” she’d ask. “Are there ways Marines can alleviate any of those stresses? Are we doing anything to make your life more difficult?”

And they responded.

“As a matter of fact, you are,” they said.

Simply by being there, they attracted the Taliban.

Those small slices of happy memories might be a nice treat for her, but for them only amounted to a small reprieve.

It’s hard, any good she accomplished can feel like a “selfish little Band-Aid,” she said.

Seeds planted

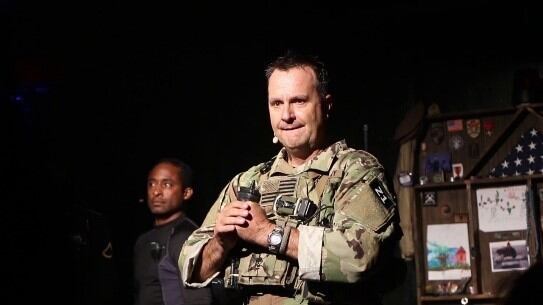

Scott Mann, 53, is a retired Army lieutenant colonel who served nearly 23 years, with most of that time as a Green Beret. He deployed to Afghanistan three times between 2005 and 2011, founded the nonprofit The Heroes Journey and authored the book, “Game Changers: Going Local to Defeat Violent Extremists.”

More recently, he worked with a group of Afghanistan veterans, “Task Force Pineapple,” to get former comrades out of the country.

On his first two deployments, the mission was hunting bad guys. There was not much of the traditional working with locals to build up a fighting force that’s the core Green Beret mission.

By the 2010 deployment, Mann was a lieutenant colonel and held the title of village stability director.

The aim had shifted.

The program borrowed from efforts in the highlands of Vietnam where Green Berets partnered with South Vietnamese villagers to fight off the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese.

His teams lived in villages, wore the same garb as locals and sat on shuras.

They started with six villages and grew to 113 villages across the country.

They helped villagers solve farming and water shortage problems during the day, he said. Then they climbed to the rooftops at night to fight the Taliban.

In a rare moment of rest, Mann sat beneath a mulberry tree with a village elder. Mann asked him what life was like before the Soviet Union invaded in 1979.

The elder looked up at the dome of the blue mosque and started crying.

“You know we used to go on the grass of the mosque every Friday and have a picnic,” the elder told him. “The kids would play and the elders would tell stories, and nobody was worried about getting shot, nobody was worried about something bad happening — and I can barely remember that. But that was what life was like, and one day it will be that way again.”

The retired soldier still holds the elder’s words as a vision of a better future in Afghanistan, and the role he and others played fueled that future, even if now it seems so distant.

“I do think seeds have been planted, not just along the ability to fight but also to govern themselves and resolve their disputes,” Mann said. “And frankly, to get a life back that so many of them have been denied.”

A foreign land, but people like me

Airman 1st Class Ashley Dent landed in Japan in 2011 for her new duty station and was promptly told she would be headed to Afghanistan in the next rotation.

The Air Force veteran and former president of her student veterans organization at New York Institute of Technology remembered what she learned in the simplest of situations — getting food each day.

When she saw Afghans working in the dining facilities it shocked her. She assumed U.S. workers would be serving food. The body language and cultural differences put her on edge.

But soon she chatted with the food workers. A young man, short with dark hair and a medium build would share his dreams of college.

One day he wasn’t there. She asked others about him.

“Oh yeah, he died,” an Afghan man said. “A motorcycle accident.”

“He showed me a picture of him,” she said.

“Oh yeah, that’s him,” she said. “He was just here yesterday.”

They started laughing.

The casual way they tossed off his death jarred her. Later, she understood, there was so much death.

That young man, in his early twenties like her, made her see the Afghans in a new light, they were like her, wanting other things in life.

“Of course, there are bad guys but there are guys on the base just trying to make a living for their family,” she said.

She lived on Bagram Air Base when the United States killed Osama bin Laden. The mortar attacks that followed seemed endless.

“When we would get hit they would be running for cover just like we were,” she said.

Protecting schools, did it help?

Nick Riffel, 32, served two tours in Afghanistan between 2009 and 2012.

Riffel now works as the national security policy advisor for The American Legion, which was involved with advocating for veterans and Afghan allies during the withdrawal.

Heading into his first deployment he had hope. Then 6th Marine Regiment went into the massive Battle of Marjah. Forty-five Marines died, many more were injured, an estimated 70 or more Afghan soldiers perished.

They did the things Marines do — root out the enemy and fight.

When he returned to Helmand province a year later as a corporal and infantry team leader, “the whole vibe was different,” he said.

The deployment was more about security for humanitarian efforts. This included a school where interpreters assigned to his unit taught reading, writing and math to children ages six to 10.

“Two out of three times we’d get shot at, we’d get lit up in that position and it was directly related to the Taliban not wanting the children to have, especially, a Western-style education,” Riffel said.

Riffel saw wide cultural gaps. In America, educating the young is paramount. In farming-centric rural Afghanistan, another body doing farm work made a difference.

Fathers would ask him, why do you put my child in school? They wanted the young ones working the fields.

“But the kids liked it,” he said.

He’s heard echoes of his own experience since then among Vietnam War veterans, saying local Vietnamese villagers told them the same thing.

Before he finished his second tour, Riffel was shot up so badly he had to be medically evacuated.

“I wanted to do right by kids, I wanted to do right by them in my Western way of thinking and everything like that, but if someone had to put me on the spot and say, ‘Did this happen? Did this help?’ I would say probably not,” he said.

Medicine, sewing machines and laughter

Memories of Mannion’s two deployments linger, more than a decade after the first.

She still smells the bazaar — burning trash, burlap sack, dust, and food cooking in oil.

On one trip, Navy medical personnel treated a child with burns on his feet from a cooking fire. That small task, one that would be an easy fix in the United States, could result in infection and death in rural regions of Afghanistan. On others, giving simple things like Motrin to a dying, elderly woman helped to ease her pain.

“’This isn’t sustainable, they’re going to run out of the medicine,’” she told herself.

But, she also saw that, if only for a moment or two, they were able relieve small sufferings, let women vent their problems, connect and play with the children.

Her team worked to get foot-pump sewing machines and fabric. They got the grunts to ask village men if their wives knew how to sew.

She laughs at the memory.

“I know you guys were stuck in a firefight this morning but I need you to help me assemble this big iron sewing machine,” she said.

Electricity, feasts and candy

Todd Hunter, 38, carried a weapon like any other Marine as he traversed Afghanistan. But he also carried a video camera. The combat correspondent joined the Corps in 2005 and was deployed to Afghanistan a few years later.

Hunter now works as a spokesman for Disabled American Veterans.

During his 2008 Afghanistan deployment, the corporal saw villagers gather in a corner of the rural countryside to see the flicker of modernity.

On one of his trips shooting videos of military and humanitarian projects, troops and workers had gotten an old electricity plant running again.

“I just remember people wanting to see electricity. Wanting to see a light bulb turn on, things we take for granted, the kind of joy it brought them,” he said.

His job meant moving from one forward operating base to another, but what his travels lacked in time, they made up for in variety.

Every few months, a local businessman who printed materials for coalition forces, delivered a delicious buffet of Afghan food — rice, lamb curry, flatbread and a creamy dipping sauce with a mound of brown sugar — “which was just amazing when you added that to it,” he said.

There were many instances of small and large efforts, kindnesses even. Now they blur together.

But even the good could hurt.

Two distinct experiences remain fixed in his memory.

On one trip Marines began handing out toys to children, first the younger girls and boys, then to older children. But they ran out. Not all of the older boys got toys.

As they drove away, he watched a girl, maybe 6 years old, walking with a pink bunny rabbit she’d received. Then he saw a teenage boy walk up, sucker punch her and snatch the toy.

“That’s one of the images I’ll never forget,” he said.

But there’s another connection he made, however brief.

In the area of Afghanistan where he was that day in 2008, women who were sent to prison often took their children with them.

In the Parwan provincial prison a boy, perhaps 4 years old, was there with his mother. Hunter tried to carry candy with him when he traveled. That day when he saw the boy he had one piece left in his pocket.

He handed it to the boy.

“And he lit up when I gave him that candy,” Hunter said.

Then he patted the child on the head and walked away.

Editor’s note: Due to an editing mistake, this story has been changed to correct numbers on the costs of the war.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.