Somewhere off the coast of a tiny island in the South China Sea small robotic submarines snoop around, looking for underwater obstacles as remotely-controlled ships prowl the surf. Overhead multiple long-range drones scan the beachhead and Chinese military fortifications deeper into the hills.

A small team of Marines, specially trained and equipped, linger farther out after having launched from their amphibious warship, as did their robot battle buddies to scout this spit of sand.

Their Marine grandfathers and great-grandfathers might have rolled toward this island slowly, dodging sea mines and artillery fire only to belly crawl in the surf as they were raked with machine gun fire, dying by the thousands.

But in the near-term battle, suicidal charges to gain ground in a fast-moving battlefield is a robot’s job.

RELATED

This imagined scenario involves a host of platforms, teamed with in-the-flesh Marines, moving rapidly across wide swaths of the Pacific. Those small teams of maybe a platoon or even a squad could work alongside robots in the air, on land, sea and undersea, to gain a short-term foothold that then could control a vital sea lane Chinese ships would have to bypass or risk sinking simply to transit.

It’s a bold, technology-heavy concept that’s part of Marine Corps Commandant Gen. David Berger’s plan to keep the Corps relevant and lethal against a perceived growing threat in the rise of China in the Pacific and its increasingly sophisticated and capable Navy.

In his planning guidance, Berger called for the Marines and Navy to “create many new risk-worthy unmanned and minimally manned platforms.” Those systems will be used in place of and alongside the “stand-in forces,” which are in range of enemy weapons systems to create “tactical dilemmas” for adversaries.

“Autonomous systems and artificial intelligence are rapidly changing the character of war,” Berger said. “Our potential peer adversaries are investing heavily to gain dominance in these fields.”

And a lot of what the top Marine wants makes sense for the type of war fighting, and budget constraints, that the Marine Corps will face.

“A purely unmanned system can be very small, can focus on power, range and duration and there are a lot of packages you can put on it — sensors, video camera, weapons systems,” said Dakota Wood, a retired Marine lieutenant colonel and now senior research fellow at The Heritage Foundation in Washington, D.C.

The theater of focus, the Indo-Pacific Command, almost requires adding a lot of affordable systems in place of more Marine bodies.

That’s because the Marines are stretched across the world’s largest ocean and now face anti-access, area-denial, systems run by the Chinese military that the force hasn’t had to consider since the Cold War.

“In INDOPACOM, in the littorals, the Marine Corps is looking to kind of outsource tasks that machines are looking to do,” Wood said. “You’re preserving people for tasks you really want a person to handle.”

The Corps’ shift back to the sea and closer work with the Navy has been brewing in the background in recent years as the United States slowly has attempted to disentangle itself from land-based conflicts in the Middle East. Signaling those changes, recent leaders have published warfighting concepts such as expeditionary advanced based operations, or EABO, and littoral operations in contested environment.

EABO aims to work with the Navy’s distributed maritime operations concept. Both allow for the U.S. military to pierce the anti-access, area denial bubble. The littoral operations in contested environment concept makes way for the close-up fight in the critical space where the sea meets the land.

That’s meant a move to prioritize the Okinawa, Japan-based III Marine Expeditionary Force as the leading edge for prioritizing Marine forces and experimentation, as the commandant calls for the “brightest” Marines to head there.

Getting what they want

But the Corps, which traditionally has taken a backseat in major acquisitions, faces hurdles in adding new systems to its portfolio.

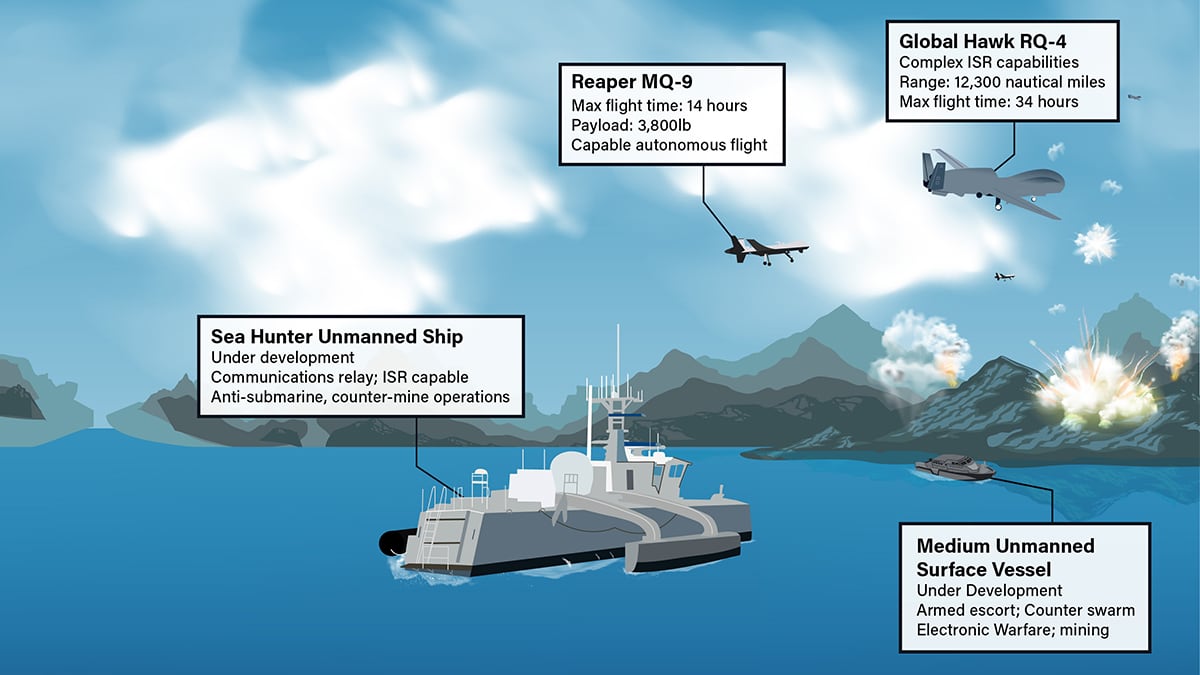

It was only in 2019 that the Marines gained more funding to add more MQ-9 Reaper drones. The Corps got the money to purchase its three Reapers in this year’s budget. But that’s a platform that’s been in wide use by the Air Force for more than a decade.

But that’s a short-term fix, the Corps’ goal remains the Marine Air-Ground Task Force unmanned aircraft system, expeditionary, or MUX.

The MUX, still under development, would give the Corps a long-range drone with vertical takeoff capability to launch from amphib ships that can also run persistent intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, electronic warfare and coordinate and initiate strikes from other weapons platforms in its network.

Though early ideas in 2016 called for something like the MUX to be in the arsenal, at this point officials are pegging an operational version of the aircraft for 2026.

Lt. Gen. Steven Rudder, deputy commandant for aviation, said at the annual Sea-Air-Space Symposium in 2019 that the MUX remains among the top priorities for the MAGTF.

Sustain and distract

In other areas, Marines are focusing on existing platforms but making them run without human operators.

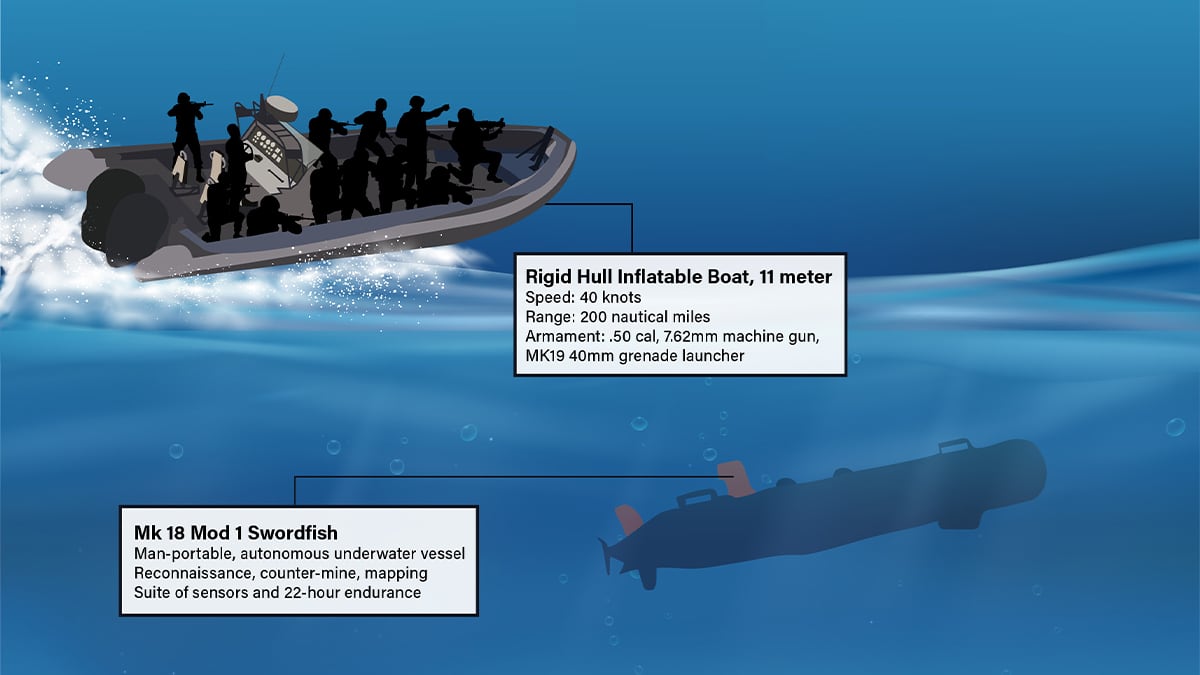

One such project is the expeditionary warfare unmanned surface vessel. Marines are using the 11-meter rigid-hull inflatable boats already in service to move people or cargo, drop it off and return for other missions.

Logistics are a key area where autonomous systems can play a role. Carrying necessary munitions, medical supplies, fuel, batteries and other items on relatively cheap platforms keeps Marines out of the in-person transport game and instead part of the fight.

In early 2018 the Corps conducted the “Hive Final Mile” autonomous drone resupply demonstration in Quantico, Virginia. The short-range experiment used small quadcopters to bring items like a rifle magazine, MRE or canteen to designated areas to resupply a squad on foot patrol.

The system used a group of drones in a portable “hive” that could be programmed to deliver items to a predetermined site at a specific time and continuously send and return small drones with various items.

Extended to longer ranges on larger platforms and that becomes a lower-risk way to get a helicopter’s worth of supplies to far-flung Marines on small atolls that dot vast ocean expanses.

Shortly after that demonstration, the Marines put out requests for concepts for a similar drone resupply system that would carry up to 500 pounds at least 10 km. It still was not enough distance for larger-scale warfighting, but is the beginnings of the type of resupply a squad or platoon might need in a contested area.

In 2016, the Office of Naval Research used four rigid-hull inflatable boat with unmanned controls to “swarm” a target vessel, showing that they can also be used to attack or distract vessels.

And the distracting part can be one of the best ways to use unmanned assets, Wood said.

Wood noted that while autonomous systems can assist in classic “shoot, move, communicate” tactics, they sometimes be even more effective in sustaining forces and distracting adversaries.

“You can put machines out there that can cause the enemy to look in that direction, decoys tying up attention, munitions or other platforms,” Wood said.

And that distraction goes further than actual boats in the water or drones in the air.

As with the MUX, the Corps is looking at ways to include electronic warfare capabilities in its plans. That allows for robotic systems to spoof enemy sensors, making them think that a small pod of four rigid-hull inflatable boats appear to be a larger flotilla of amphib ships.

Overreliance

Marines fighting alongside and along with semi-autonomous systems isn’t entirely new.

In communities such as aviation, explosive ordnance disposal and air defense, forms of automation, from automatic flight paths to approaching toward bomb sites and recognizing incoming threats, have been at least partly outsourced to software and systems.

But for more complex tasks, not so much.

How robots have worked and will continue to work in formations is an evolutionary process, according to former Army Ranger Paul Scharre, director of the technology and national security program at the Center for a New American Security and author of, “Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War.”

If you look at military technology in history, the most important use for such tech was in focusing on how to solve a particular mission rather than having the most advanced technology to solve all problems, Scharre said.

And autonomy runs on a kind of sliding scale, he said.

As systems get more complex, autonomy will give fewer tasks to the human and more to the robot, helping people better focus on decision-making about how to conduct the fight. And it will allow for one human to run multiple systems.

When you put robotic systems into a squad, you’re giving up a person to run them and leaders have to decide if that’s worth the trade off, Scharre said.

The more remote the system, the more vulnerable it might be to interference or hacking, he said. Built into any plan for adding autonomous systems there must be reliable, durable communication networks.

Otherwise, when those networks are attacked the systems go down.

That means that a Marine’s training won’t get less complicated, only more multifaceted.

RELATED

Just as Marines continue to train with a map and compass for land navigation even though they have GPS at their fingertips, Marines operating with autonomous systems will need continued training in fundamental tactics and ways to fight if those systems fail.

“Our preferred method of fighting today in an infantry is to shoot someone at a distance before they get close enough to kill with a bayonet,” Scharre said. “But it’s still a backup that’s there. There are still bayonet lugs on rifles, we issue bayonets, we teach people how to wield them.”

Where do they live?

A larger question is where do these systems live? At what level do commanders insert robot wingmen or battle buddies?

Purely for reasons of control and effectiveness, Dakota Wood said they’ll need to be close to the action and Marine Corps personnel.

But does that mean every squad is assigned a robot, or is there a larger formation that doles out the automated systems as needed to the units?

For example, an infantry battalion has some vehicles but for larger movements, leaders look to a truck company, Wood said. The maintenance, care, feeding, control and programming of all these systems will require levels of specialization, expertise and resources.

The Corps is experimenting with a new squad formation, putting 15 instead of 13 Marines in the building block of the infantry. Those additions were an assistant team leader and a squad systems operator. Those are exactly the types of human positions needed to implement small drones, tactical level electronic warfare and other systems.

The Marine Corps leaned on radio battalions in the 1980s to exploit tactical signals intelligence. Much of that capability resided in the larger battalion that farmed out smaller teams to Marine Expeditionary Units or other formations within the larger division or Marine Expeditionary Force.

A company or battalion or other such formation could be where the control and distribution of autonomous systems remains.

But, current force structure moves look could integrate those at multiple levels. Maj. Gen. Mark Wise, deputy commanding general of Marine Corps Combat Development Command, said recently that the Corps is considering a Marine littoral regiment as a formation that would help the Corps better conduct EABO operations.

Combat Development Command did not provide details on the potentially new regimental formation, confirmed that a Marine littoral regiment concept is one that will be developed through current force design conversations.

RELATED

A component of that could include a recently-proposed formation known as a battalion maritime team.

Maj. Jake Yeager, an intelligence officer in I MEF, charted out an offensive EABO method in a December 2019 article on the website War On The Rocks titled, “Expeditionary Advanced Maritime Operations: How the Marine Corps can avoid becoming a second land Army in the Pacific.”

Part of that includes the maritime battalion, creating a kind of Marine air-sea task force. Each battalion team would include three assault boat companies, one raid boat company, one anti-ship missile boat battery and one reconnaissance boat company.

The total formation would use 40 boats, at least nine which would be dedicated unmanned surface vehicles, while the rest would be developed with unmanned or manned options, much like the rigid-hulled inflatable boats which the Corps is currently experimenting with.

Illustrations by Jacqueline Belker/Staff

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.