Michael Langley and his track teammates were running through practice drills, working to shave time off their sprints at the University of Texas at Arlington.

He was a 400-meter sprinter. Many see it as one the hardest races. It’s a longer distance than the 100-meter and 200-meter dashes, but still requires all-out effort. It takes a special kind of perseverance.

A Marine gunnery sergeant walked up to Langley and his teammates with a pitch.

“What do you guys run the 400-meter in?” the gunny asked.

The gunny promised they’d cut at least a second off their best times if they tried the Platoon Leaders Class — an entry point for officer training at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Virginia — and ran with gear through the woods in six weeks of grueling training.

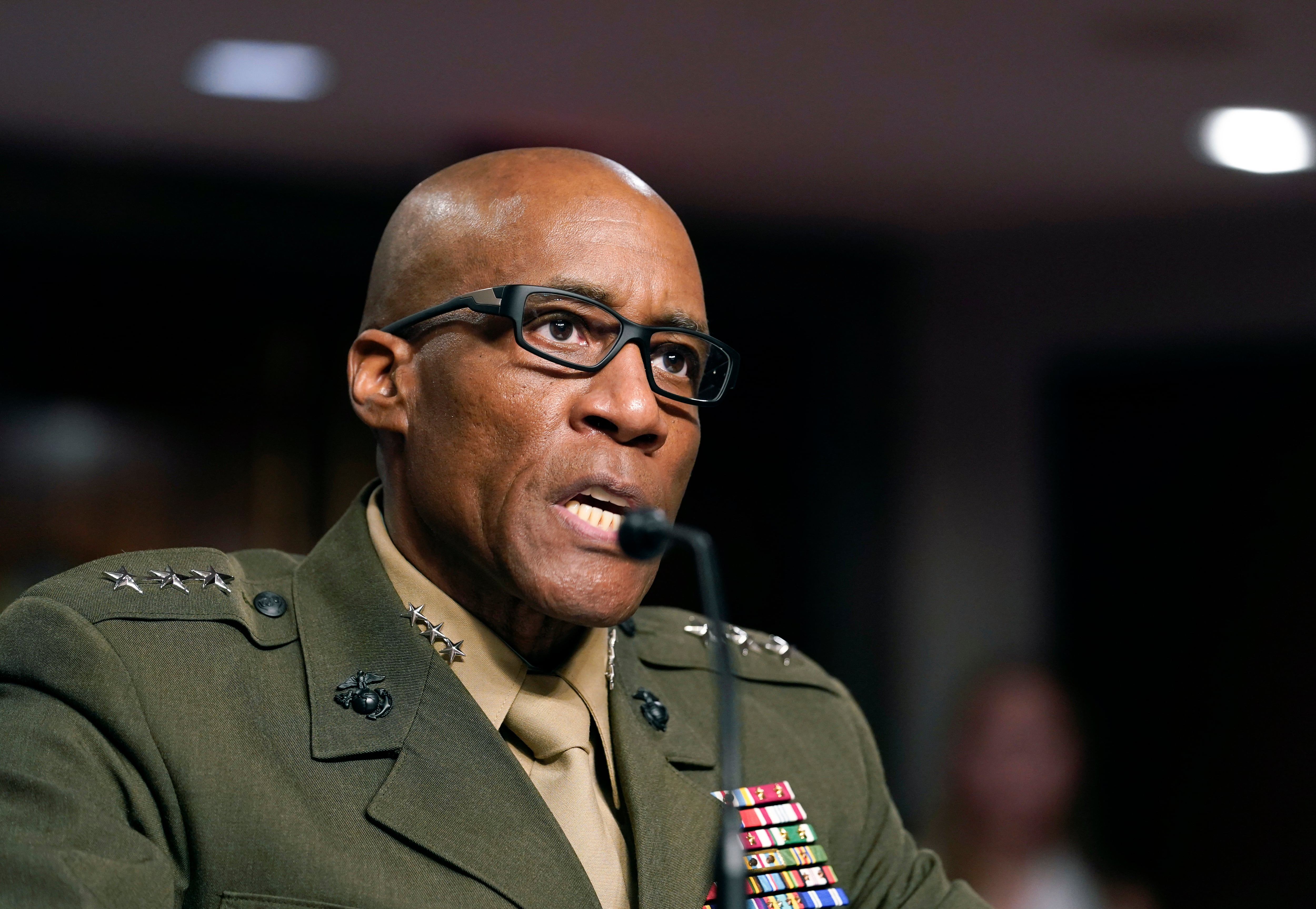

“So, I went to the Platoon Leaders Class in the summer of 1983,” Gen. Michael E. Langley told Marine Corps Times in August. “That changed my life.”

On Aug. 6, 2022, Gen. Michael E. Langley became the first Black four-star in Marine history.

RELATED

Much like his track race, his Marine career required its own special pacing.

Many times, retirement called. But the Shreveport, Louisiana, native tackled each new demand with a vigor, problem-solving intellect and work ethic matched by few, his fellow Marines have said.

“Mike Langley was one of those guys who was told to go and do something really hard, and he said, ‘Aye, aye sir and he did it,” retired Lt. Gen. Mark A. Brilakis told Marine Corps Times.

Those “really hard” assignments included volunteering with youth, taking units to combat, commanding the 12th Marine Regiment, running training for Marine Expeditionary Units, late nights in the Pentagon’s bowels on cost-cutting missions and heading Marine Forces Command before recently taking over U.S. Africa Command in a time of strained resources and increasing operational demands.

Langley is now one of 74 Marines who’ve held the four-star rank. And several of those were “tombstone generals,” having been promoted in retirement or posthumously.

His achievement stands in stark contrast to comments of the Corps’ first four-star, 17th Commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. Thomas Holcomb.

Holcomb served from 1900–1944, rising to the top post in 1936 and leading the Corps through its most transformative period, growing from fewer than 20,000 to more than 475,000 Marines under his tenure.

Despite those manpower demands, Holcomb held a firm view: The Marine Corps had no room for Black servicemen.

“If it were a question of a Marine Corps of 5,000 whites or 250,000 Negroes, I would rather have the whites,” Holcomb told the Navy General Board in April 1941.

While the men may share a rank, Holcomb never served with four stars. He ended his career as a lieutenant general. His fourth star came in retirement.

A decision

Shortly after the gunny confronted Langley and his teammates on the college track, Langley spoke to the officer selection officer about the details.

“Do you want to lead Marines on the other side of the world?” the Marine had asked. “Or do you want to take the job in the corporate world and be a programmer in a cubicle somewhere in downtown Dallas-Fort Worth (Texas)?”

“It was an easy choice,” Langley said.

The son and younger brother of Air Force veterans, Langley jokes that his father taught him early to “aim high,” the service’s motto.

“So, I aimed high and found the Few and the Proud,” Langley said. “He was kind of bothered that I selected the Marine Corps, but he’s probably the most proud Marine Corps poppa right now.”

Langley commissioned in 1985 and became an artillery officer.

The Marine Corps promotes more of its best to the general officer ranks from combat arms. It is a war-fighting organization and commanding combat troops has held a premium from its inception.

Like many, Langley didn’t plan to become a general. Even if he had, the winnowing process, a combination of hard work, the right postings and some luck can derail those ambitions.

When he reached Hotel Company, 3rd Battalion, 10th Marine Regiment, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, the young officer got a feel for what command meant.

“I’d say my first experience to be able to lead a guns platoon for a gun section was probably the inaugural piece of, hey, this is what that officer selection officer was talking about,” Langley said.

Langley faced an early setback when assigned to the Marine Barracks, Washington. Despite his best efforts he was not selected to lead Marines in the coveted evening parades of the Silent Drill Platoon at 8th and I.

That was in the early 1990s. Washington faced alarming levels of crime and violence and the sustained drain of the crack-cocaine scourge on underprivileged neighborhoods.

Retired Lt. Gen. Ronald Bailey, then a major who would later go on to be the first Black commander of 1st Marine Division, took Langley aside.

“I called him my ‘mission man,’” Bailey told Marine Corps Times. “This guy was given a task and can do it better than anyone.”

Langley had taken on an extra duty at Bailey’s suggestion. He was leading 200 local “Young Marines,” a national nonprofit youth organization focusing on leadership and community service.

Bailey told the young captain the work he did with the group meant more than the parades they held.

“We shaped their attitudes, shaped their personality, we become role models and I want them to see a guy who looks good in uniform, who was very articulate, very smart, very driven, very purpose focused,” he said.

Langley would leave the Barracks and go on to command units at every step of the ladder.

After multiple combat and overseas deployments, Langley faced another critical junction that hundreds of Marine officers face in a long enough career: the leap from colonel to brigadier general.

A new kind of challenge

Langley again weighed his options. He’d put a quarter century of his life into the Corps. Combat deployments? He’d done a few. Commanding and training tactical units? Check that box. Aide to future Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Peter Pace. Yes, sir.

But corporate America could really make his life easy. It seemed as though every time he attended recruiting events or functions for the Corps, the siren song of a higher salary and more stable lifestyle beckoned.

“But to me it wasn’t fulfilling just thinking of jumping ship at the 10-year mark or even the 20-year mark and making more money because it wasn’t as satisfying or fulfilling as the Marine Corps,” Langley said.

In Okinawa, Japan, in the late 2000s, Langley oversaw the Special Operations Training Group for the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit. That MEU would see multiple trips to the Philippines, tsunami and other disaster responses, balancing many of the Corps’ Pacific needs while other wars and crises raged.

Then-Brig. Gen. Mark Brilakis would sometimes drop by Langley’s office, plop in the chair and query the promising colonel about his plans.

“He had done most of the things he wanted to do in the Marine Corps,” Brilakis said.

Langley could stay at the Marine expeditionary force staff level. It’s a high distinction and many end a fine career there, but it wouldn’t have led to the next level, Brilakis said.

“You need to do something hard,” Brilakis had told him.

Hard? Let’s recap — Langley had commanded at nearly every tactical level and rubbed shoulders with some of the most powerful, high-ranking Marines in the Corps’ history.

Also a combat arms Marine, Bailey called the artillery field unforgiving.

An unsafe fire decision means getting fired. Bad maintenance logs mean you get fired. Your unit can’t keep up with supplies or fast moving battle plans — fired.

“He survived in an artillery field where you don’t get second chances,” Bailey said.

But Brilakis meant a different kind of hard — the dollars and cents of running a lean Marine Corps.

Langley shouldered his ruck and put in for a job at Programs and Resources.

He arrived at the Pentagon, reporting to Lt. Gen. John Wissler. It was 2010, as Afghanistan heated up, Iraq wound down. The Corps faced demands as it hadn’t seen since Vietnam.

“Wissler told me, you are going to be the efficiencies guy across the Marine Corps,” Langley said.

That meant traveling the Corps to tell already strapped commanders they had to cut more.

“There’s no guy in the world who wants to be the assistant deputy commandant for programs and resources, nobody,” Brilakis said.

Langley worked those numbers, telling people what they didn’t want to hear. Such as his look at the expeditionary fighting vehicle, the replacement for the cherished, but aging, amphibious assault vehicle.

The Marines wanted it, maybe needed it. And after decades of development and more than $3 billion in spending, the Corps expected it by 2015. Based in part on Langley’s recommendation, then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates canceled it.

“You can lose friendships,” Brilakis said. “It’s not easy work.”

Race and the Corps

The Marine Corps was the last military branch to accept Black recruits and it put those recruits in all-Black training units at Montford Point, North Carolina, beginning in 1942.

The units remained segregated, despite combat performance in the Pacific. The Montford Point camp was decommissioned in 1949 as Black Marines integrated into the force.

Another Marine trailblazer shared his view of the Corps and race with Marine Corps Times.

“It’s interesting that it took 40 years for Frank Peterson to get his first star and now, 40 years later, Gen. Langley is getting his fourth star,” said Montford Point Marine and former U.S. Ambassador Theodore R. Britton Jr.

Lt. Gen. Frank Peterson was the first Black Marine aviator and the Corps’ first Black general officer, promoted to brigadier general in 1979.

In comparison, the Air Force had promoted Daniel “Chappie” James to four-star general in 1975.

Many of today’s Marine colonels started their career paths more than two decades ago. For generals that could be as far back as the 1980s.

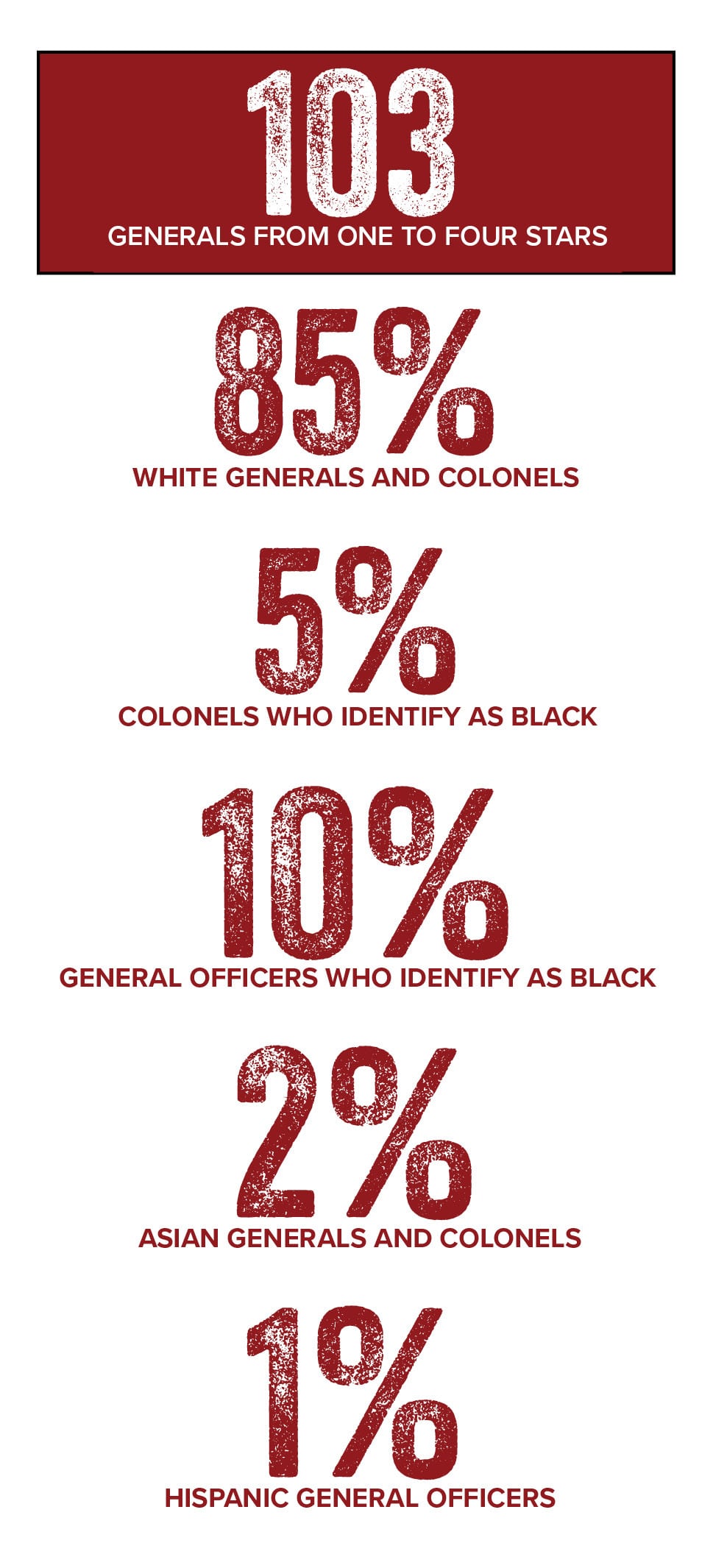

There are 883 colonels and 103 general officers total in the combined active and reserve Marine Corps currently, according to Marine Corps Manpower and Reserve Affairs.

For both colonels and all ranks of general officers, 85% are white. Forty-six, or 5% of colonels, identify as Black, while nearly 10% of general officers, or 10, identify as Black.

For colonels and general officers about 2% identify as Asian, while nearly 4% of colonels and 1% of general officers identify as Hispanic.

But Britton noted it hadn’t always been that way.

An enlisted Marine with service in both World War II and Korea, he applied for a commission but said when the promotion board discovered he had fought publicly against segregation, he was turned down.

“I’m so happy for (Langley) and for the Corps,” Britton said. “It’s been improving all along. The country’s been improving too, but especially the Marine Corps.”

Langley acknowledged the historic significance of his promotion in an interview with Marine Corps Times, but he pushed back on race having created hurdles in his career path. Instead, he referenced the opportunities he’s had.

But he worries that some underrepresented populations both in and outside of the Marines have a misconception of the Corps and their place in it.

“There are opportunities built on meritocracy,” Langley said.

Langley values diversity, he said, but not only of race.

“Operational excellence comes from a diverse group, whether in gender, or even race, collectively, the Marine Corps gets greater value on a collective set of diverse individuals coming together as a unified team,” he said.

What’s next?

The process from colonel to one-star is brutal.

But Langley’s work proved its worth.

Out of hundreds of Marine colonels reviewed for brigadier general promotion each year, sometimes only 10 are chosen, Wissler, now retired, said. Those selected learn early that they’re special, but just barely.

At the brigadier general officer orientation Wissler attended, the message was clear.

“They tell you if 10 of you are killed in a bus crash, we can find 10 just as good,” Wissler said.

The pace only quickens.

“The commandant tells you, ‘Congratulations, enjoy the moment,” Wissler said. “But from the time you pin on you get on the treadmill and there are only two buttons — faster and increase elevation.”

After pinning his first star, Langley went on to serve as deputy commanding general of II Marine Expeditionary Force and later led Marine Forces Command and Marine Forces Northern Command in 2021.

Col. Reginald McClam, recently appointed commander of The Basic School at Quantico, Virginia, first met Langley when the general led 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

McClam told Marine Corps Times that he’d known of Langley by reputation for years.

Coming up as a Black infantry officer in the mid-1990s, McClam didn’t see many in his same boots in that job field.

RELATED

“For whatever reason, he just naturally grabbed me as a mentee,” McClam said.

The colonel attended Langley’s promotions to both three and four star.

“What that does is it shows people you can do it,” McClam said. “Young lieutenants can sit inside Henderson Hall and look and go, ‘I can be a Gen. Langley,’ agnostic of their race, creed, color, religion, they see a general officer who did it.”

Washington rumors percolated this past summer that Langley would be nominated to serve as commander of U.S. Africa Command. He attended confirmation hearings in July.

In the whirlwind that followed, Langley returned to the Washington Barracks for his promotion to general by Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. David Berger, and then off to his new home in Stuttgart, Germany, headquarters of AFRICOM.

In a force where all but one who has reached four stars are white males, seeing different faces in those positions matters.

“The Marine Corps needs African American generals, and we need more,” Brilakis said. “We’ve got a lot of young kids who look up and they get inspired by the Marine Corps early and they look around for people they can aspire to and it’s necessary that we have all sorts of folks in the senior leader ranks to provide aspiration for others.”

The diversity of thinking, backgrounds and experience also matters, Langley said. And he wants Marines to know it.

The defense department needs the Marine Corps as much now as ever, he said. Especially as the Pentagon pivots to a new kind of combat and competition landscape. A diverse Marine Corps can better deliver on that tasking.

“And these young Marines, if they want to be part of something special, they will stay Marine,” he said.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.