Editors Note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service, under the headline “They’ve Never Been Arrested. Why Does the FBI List Thousands of Service Members as Potential Criminals?” Subscribe to their newsletter.

Denise Rosales has never been arrested.

She’s never been handcuffed.

She’s never spent a night behind bars, never stood before a judge to profess her innocence.

And yet, if you perform a background check, a criminal database maintained by the FBI will say that she was “arrested or received” into custody and charged with three crimes in January 2021.

While deployed in Kuwait, Rosales, a member of the Texas Army National Guard, threw a birthday party for her husband. Some of the guests allegedly brought alcohol, according to the Army, “in a nation where such substances are illegal.” She was investigated and fingerprinted by an Army investigator, but received nothing more than an administrative reprimand.

Still, more than four years later, the Texas mother of two is fighting to clear her name. She’s been forced out of her full-time position with the National Guard on a multiagency counterdrug task force, lost job opportunities, and even denied the chance to chaperone her kids on school field trips.

Rosales’ saga is the result of a perplexing record-keeping process the military justice system calls “titling”—and it’s one that’s left potentially thousands of veterans saddled with false criminal histories, according to a lawsuit against the Army and Department of Defense.

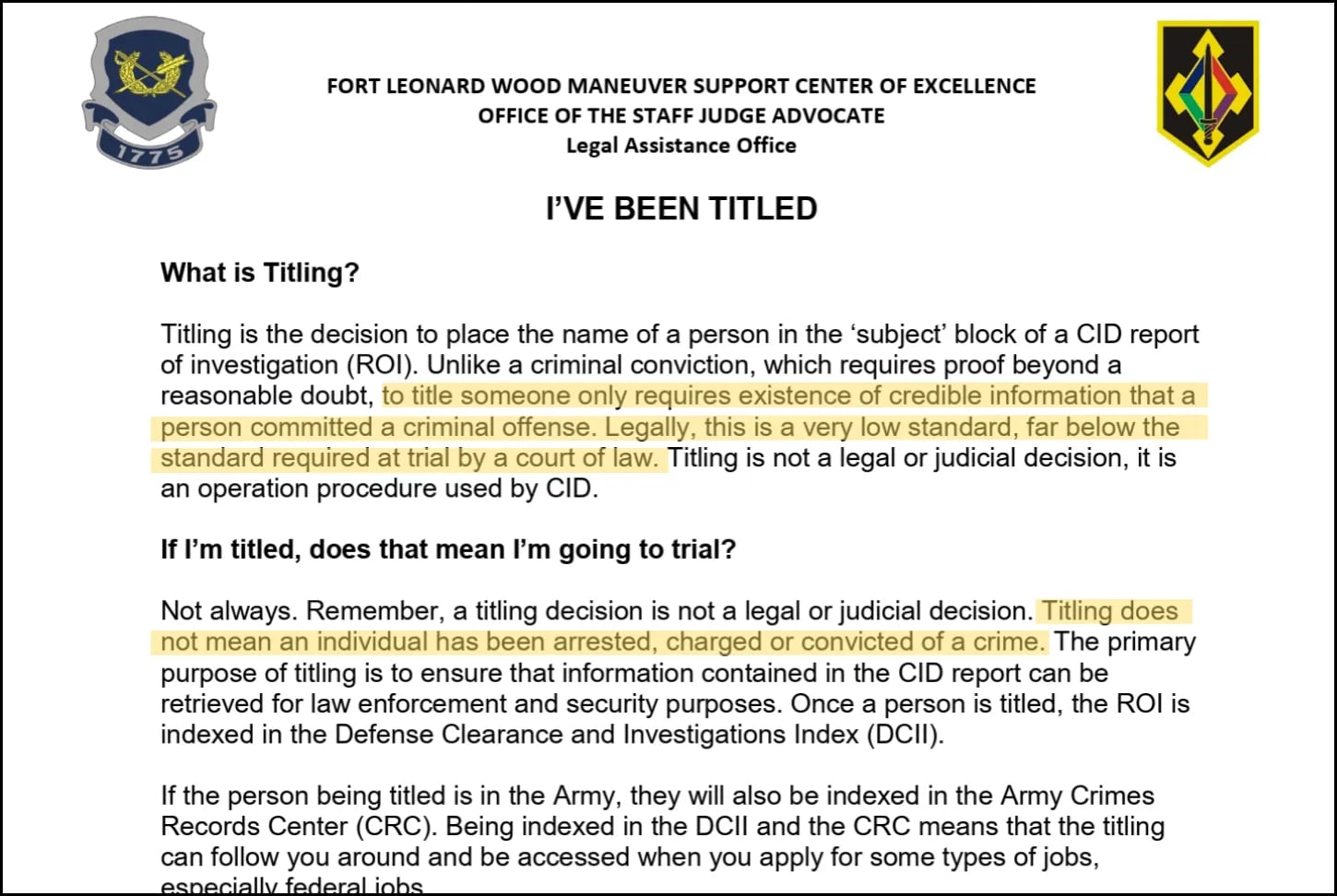

The term sounds nonthreatening enough. But in the military, “titling” isn’t about taking ownership of a car or property. It’s what happens when a service member’s name is simply listed as the “subject” in a military criminal investigative report. “Titling does not mean an individual has been arrested, charged or convicted of a crime,” a legal assistance document on the Army’s website explains.

But here’s the problem: Every branch of the military shares titling records in criminal databases with more than two dozen agencies, including the FBI, even if the case was dropped.

The fallout can be devastating because the records are retrievable for decades. Veterans can be passed over for promotions, rejected on apartment applications, and denied firearms clearance, advocates say. With the stain on their record, some struggle to get a job for years.

“Who will take my word over the plain text of the FBI’s criminal history?” Rosales, 39, asks in an affidavit in her lawsuit.

She feels betrayed, thinking back to the day when a military recruiter came to her school when she was 17. “I was told the military would guide me in the right direction and have my back,” Rosales told The War Horse.

With the Army refusing to budge, Rosales’ case has become a showdown over the military’s system of titling. Veterans and civil liberties advocates are calling for reforms while victims’ groups stress the need for the military to alert civilian law enforcement and employers of the danger among their ranks.

But during a hearing in the ongoing lawsuit, a judge posed a fundamental question about the service members and veterans like Rosales being wrongfully tagged by the military justice system that even the government’s attorney was unable to answer:

Why “is this that big a deal to the Army?”

How big a problem is titling?

It’s hard to know how many people have been caught up in the quagmire, because there is no requirement to notify service members they’ve been titled, and many don’t find out for years until it turns up, for example, when someone tries to buy a gun, travel abroad, or apply for a job.

The War Horse has filed Freedom of Information Act requests for records from the Department of Defense and National Archives, which houses military criminal files, to reveal how many people have been titled but not court-martialed, but the agencies are not responding to requests during the government shutdown.

Frank Rosenblatt, a former Army prosecutor and an associate professor at the Mississippi College School of Law, estimated the number is at least 10,000 service members and veterans.

The problem is, our military justice system doesn’t “always easily translate over into civilian terms,” said Rosenblatt, who has represented titled veterans.

In the military, titling only requires the existence of “credible information” that a crime was committed. “Legally, this is a very low standard, far below the standard required at trial by a court of law,” according to Fort Leonard Wood’s Army legal assistance office.

“In the vast majority of cases, these [investigators] are young soldiers who don’t have any significant level of criminal justice experience, but are somehow vested with tremendous authority to make determinations that follow people for the rest of their lives,” said Doug O’Connell, an Austin, Texas-based attorney who is representing Rosales.

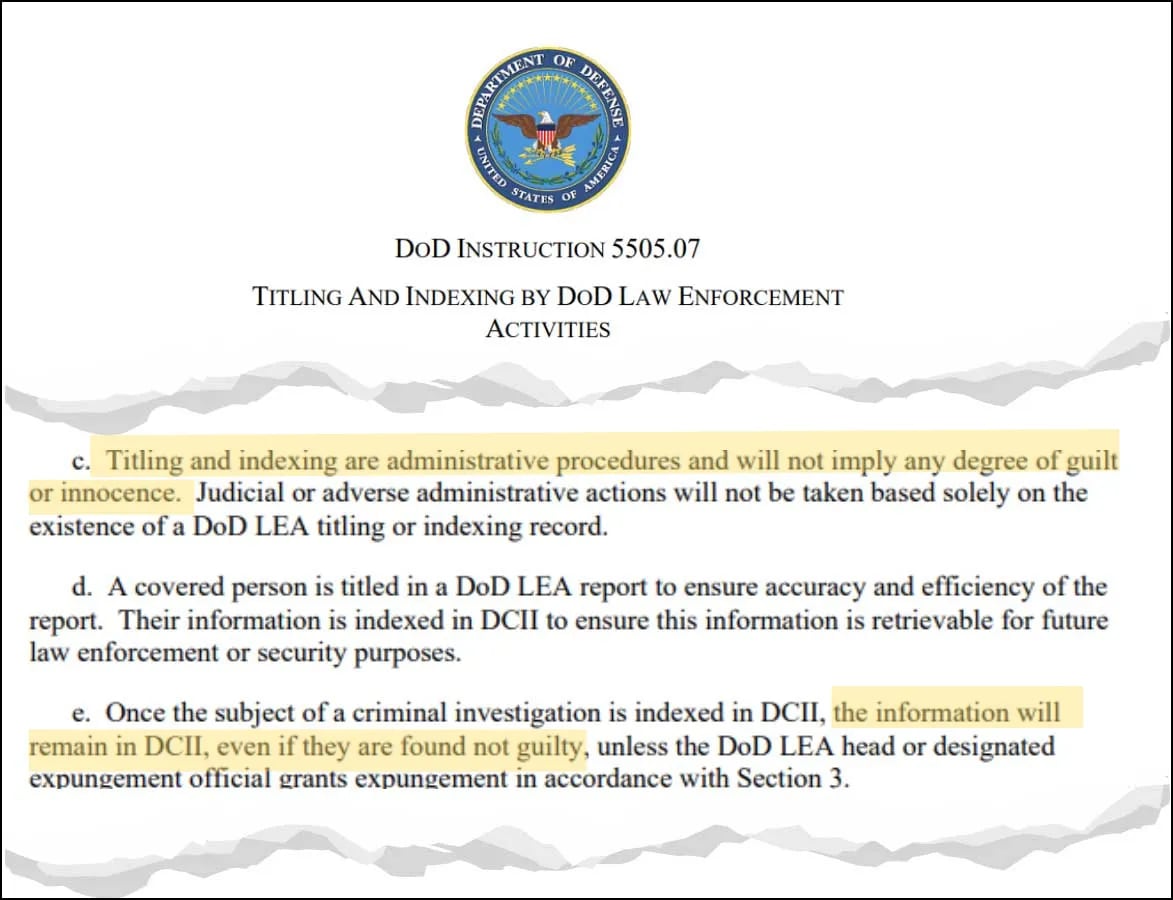

And the Department of Defense spells out the other huge hurdle for wrongfully titled service members:

“Once the subject of a criminal investigation is indexed in” the database known as the Defense Central Index of Investigations, the information remains “even if they are found not guilty”—unless DOD law enforcement officials agree to expunge the record.

But that’s a whole separate headache. To appeal, victims of titling are forced—sometimes long after they leave the military—to prove the crime didn’t happen, said O’Connell, a former Special Forces colonel in the Army who now specializes in defending military service members.

“They’ve created a system where you’re guilty until proven innocent,” he said. “If the [Army Criminal Investigation Division] agent believes something, then you’re going to have this criminal history created, and it’s up to you to now prove that it didn’t happen.”

An overcorrection?

The Army’s Criminal Investigation Division did not respond to multiple interview requests from The War Horse over more than a month of reporting. The United States Attorney’s Office, which represents the Army and DOD in Rosales’ lawsuit, declined to comment on the case, citing active litigation. The FBI, whose lawyer argued is “simply a clearinghouse” of titling information, was dismissed from the lawsuit.

But even Rosales’s legal team acknowledges the logic behind the military sharing criminal records: If someone commits a crime during their military service, civilian law enforcement should be able to know.

“I want my government to keep me safe from people who they know have a propensity for illegality or criminality or violence,” said William Thomas, one of Rosales’ attorneys and a former Army field artillery officer.

To understand why titling creates chaos in the lives of so many veterans, go back to the pews of a white church in Sutherland Springs, Texas.

Devin Kelley, an Air Force veteran with two domestic assault convictions, opened fire in November 2017 during morning services at the small community church, killing 26 people, several of them children. It was one of the deadliest mass shootings in the state’s history.

But why had Kelley been allowed to purchase his semiautomatic rifle, along with the two handguns found in his vehicle, from licensed vendors, given his criminal background?

His convictions during his military service hadn’t been entered into the national criminal background system.

The Department of Defense has long required that criminal history, including fingerprints, be shared with the FBI when a service member is investigated for an offense.

But, as it turns out, the military wasn’t very diligent about doing it. After the Texas church shootings, a Pentagon review found that one in four fingerprint cards were not submitted to the FBI, and a 1997 report by the DOD inspector general found that in the Army, fingerprint cards weren’t submitted to the FBI in more than 80% of cases.

The public demanded accountability. Victims’ families sued the federal government, arguing the Air Force had been negligent in its failure to share Kelley’s criminal background, and in 2023, the Department of Justice announced it had reached a tentative settlement of $144.5 million.

In response, the military overcorrected, O’Connell said. After the shootings, the titling problem bloomed into a widespread issue, likely affecting thousands more veterans.

The military doesn’t want anyone “to slip through the cracks,” Rosenblatt said. In the face of potential lawsuits, there’s a strong incentive to share information about veterans’ backgrounds, but “they don’t have strong incentives for people’s privacy and due process.”

Discovering his own violent arrest record

The crimes were shocking: Murder. Negligent homicide. Attempted aggravated sexual contact.

It took former Green Beret James Morris four years to get these false charges cleared from his record.

After a fellow soldier was killed during a 2017 hazing incident, one of the assailants claimed Morris had given permission for the attack. Even though Morris hadn’t been present for the assault and was never taken into custody or charged, he was fingerprinted and titled during the investigation.

Little did he know that left him with a violent arrest record. He only discovered it in 2021 when he tried to renew his concealed carry license.

While the offenses remained on his record, Morris lost his security clearance and was wary of applying for jobs. But one of the worst parts was losing pride in his service.

“They took away from me more than just my career—that’s 18 years, 10 months of memories that I can’t grapple with properly,” said Morris, who now works as a contract training analyst at Fort Gordon in Georgia.

For many veterans and service members like Rosales, the ordeal continues—undoing titling is extremely difficult, advocates say. In more than a hundred appeal cases he’s filed, O’Connell said he’s only been successful once.

Rosales first discovered she had an arrest record when she returned from Kuwait and tried to return to her National Guard-sponsored position as a drug analyst for a counterdrug task force. She sought to have her records corrected in November 2021, but the Army denied her request and appeal over the next two years.

If an “untitling” petition is denied, the next step is to appeal to the Army Board for Correction of Military Records. People have had more success in expunging their records there, O’Connell said, but the process is lengthy, due to a growing backlog of cases. It can take years to get cleared.

“It’s hard to prove your innocence,” said Liz Ullman, who launched the advocacy group Defend Our Protectors after nearly a thousand service members were caught up in a recruiting scandal. “Which is why you’re not supposed to have to.”

‘I want my children to be proud of their mother’

The fallout from Rosales’ titling record was swift and substantial.

She lost her National Guard job as a criminal analyst in a federal counterdrug task force, which she’d held for 12 years, and cut short her eligibility for retirement benefits, including a pension. In an affidavit, she said she was “reluctant to apply for other Guard employment to save myself from the embarrassment of bringing up my false criminal history.” When her security clearance comes up for renewal, she expects it will be revoked.

She sold her home and relocated her family closer to the Mexican border when a commander gave her a chance—despite her record—to work as a first sergeant for Operation Lone Star, a border security initiative launched in 2021 by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott. The false charges continued to come up, blocking her access to certain buildings, she said.

What’s even more humiliating is that she’s been unable to attend her kids’ school field trips, which require background checks.

“I want my children to be proud of their mother,” she said in the affidavit, “and not ask why I cannot attend a school event.”

Still, her case drags on. While a judge in September rejected her legal team’s petition to approve the suit as a class action case, the lawyers are still hopeful that a win in Rosales’ case could help other wrongfully titled veterans.

The Army’s refusal to correct her records hasn’t just befuddled her advocates—even the judge presiding in her lawsuit has expressed similar confusion.

‘I don’t understand why they just don’t remove it’

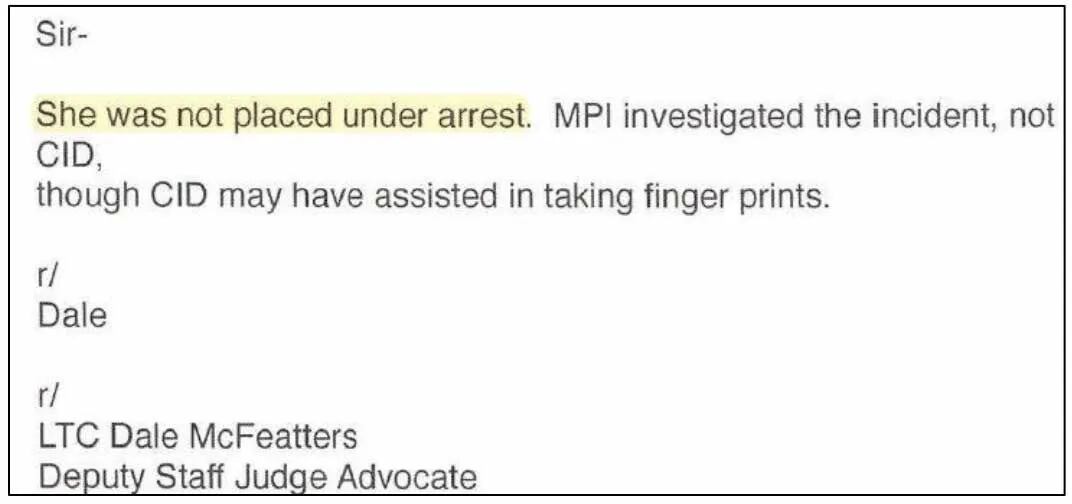

Back in May 2021, an Army JAG officer confirmed in an email to one of Rosales’ lawyers that she had not been arrested for the incident in Kuwait. Despite the acknowledgement, the Army Criminal Investigation Division denied her request and a subsequent appeal to have her records corrected.

Three years later, with her case in U.S. District court, lawyers for both Rosales and the Army were still quibbling before a judge over whether Rosales had been arrested. The Army’s lawyer, Matthew Mueller, acknowledged that although Rosales was read her rights, gave a statement, and was fingerprinted and photographed, she was never detained in jail or handcuffed.

By 37 pages into the hearing transcript, U.S. District Judge David A. Ezra seemed exasperated.

“What is a little aggravating is we don’t really have an explanation from the Army as to why they haven’t changed her record,” he said at the May 2024 court hearing. “Apparently, she wasn’t charged. I mean, I don’t understand why they don’t just remove it.”

In an order two weeks later, Ezra doubled down on his point: “Defendants provided no explanation as to why they would not change her record,” he wrote. “One could only speculate as to why the Army would defend a record that is not accurate of the events that took place.”

Now, with both sides awaiting the judge’s decision on whether the case should move to trial, frustration is mounting for Rosales and her legal team.

“Do I really have to stand in front of a federal judge, a lifetime appointee, a third co-equal branch of government, and say, ‘Judge, I just want the Army to stop lying about my client?’” asked Thomas, one of her attorneys. “Is that really how far I have to go?”

Reforming a ‘giant organizational defect’

The solution to this issue seems simple enough, advocates say: The titling process needs reform.

Derrick Miller, the director of the Congressional Justice for Warriors Caucus, which advocates for wrongly accused veterans, has lobbied for a legislative amendment that would require that titling records be deleted after 10 years if the service member will not be charged or court-martialed over the allegation. These reforms would ensure due process and prevent an accusation from having the same consequences as a conviction, Miller said.

U.S. Rep. Eli Crane, an Arizona Republican and former Navy SEAL, introduced the amendment in August.

“Far too often, the reputation of our brave service members is unfairly tarnished due to titling,” Crane told The War Horse, calling the amendment a “sensible approach to protecting the livelihoods of our courageous veterans.”

Reforming the titling system is common sense, experts say. The military’s system of titling is a “giant organizational defect,” said Robert Bracknell, a retired Marine armor officer and an adjunct professor at William & Mary Law School.

There’s little incentive for the military to change the titling process, Rosenblatt added. “This isn’t a politically powerful block of the military,” he said, referring to those who’ve been unfairly titled. “It’s often people who are on the outs with their command, and they end up being investigated.”

The issue needs a champion, Bracknell said.

Rosales could be that champion. But her team wonders why she needs to be.

“Why are they fighting so hard to preserve something so wrong?” O’Connell asks. “As a guy who spent 30 years in the Army, I’m completely disgusted.”

This War Horse story was edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.

Rachel Fobar is a freelance investigative reporter and fact checker. Previously, she was a wildlife trade investigative reporter for National Geographic, and before that, she covered criminal justice and potentially wrongful convictions for The Medill Justice Project. She has also written for the Guardian, Popular Science, and ABC News. She has won several awards for her work, including the Chicago Headline Club’s Peter Lisagor Award. She has a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University.