In the midst of the Vietnam War, U.S. troops were rocked by an offensive that saw conventional and irregular enemies sweep over territories and entrench themselves in areas of South Vietnam previously untouched by the war.

What would follow would be the most intense urban combat U.S. forces had faced since World War II.

A half century later, lessons from the Battle of Hue City are still being absorbed by today’s war fighters.

Much has changed, but much has remained the same. As Bing West, a Marine combat veteran and former assistant secretary of defense wrote, when comparing Hue and the battle for Mosul, Iraq, “urban warfare remains characterized by slow, massive destruction.”

For a long time, both the Marines and Army failed to do anything substantial to prepare for large-scale urban combat — other than to avoid it whenever possible.

But both services are now updating their urban operations doctrine for the first time in years, and their leaders, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley and Marine Corps Commandant Gen. Robert Neller, have publicly pushed for more urban-focused efforts.

More than half the world’s population lives in urban areas, according to a 2016 United Nations report. That’s only expected to rise in coming decades.

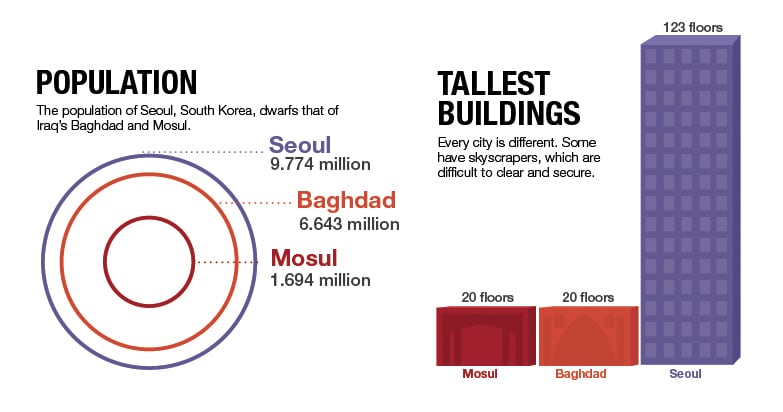

The U.S. military spent a decade fighting in Baghdad, a city with a population of about 6.5 million people. In slightly more than a decade there will be 37 cities that are two to four times that size.

With ongoing tensions in North Korea, any attack would likely include devastating effects on Seoul, a megacity of 24 million people.

Encroachments in Europe by Russia in the Baltic region directly threaten the capitals of three nations — Riga, Latvia; Tallinn, Estonia; Vilnius, Lithuania.

And growing urban areas in Africa, such as Lagos, Nigeria, and Mogadishu, Somalia, where U.S. troops deployed in the early 1990s, show a different face to urban combat.

Troops have many more tools in their hands than they did decades ago.

At the same time, some of the more effective means by which troops won back Hue — flamethrowers, CS gas and devastating short-range, vehicle-mounted recoilless rifle systems to complement tanks — are no longer in the arsenal.

While there is much work being done, some are skeptical about when and how that will reach troops.

“We can update doctrine all we want, soldiers don’t read doctrine unless there’s a forcing function,” said Maj. John Spencer, a career infantry officer who rose from the enlisted ranks.

For Spencer, the forcing function will be when the Army dedicates training centers, materiel and staff to becoming experts at urban war fighting.

Renewed Focus

Milley has said the Army is not ready to fight in megacities. He has characterized recent and current urban operations, including fighting in Aleppo in Syria, and Fallujah and Mosul in Iraq as “previews” of future conflict.

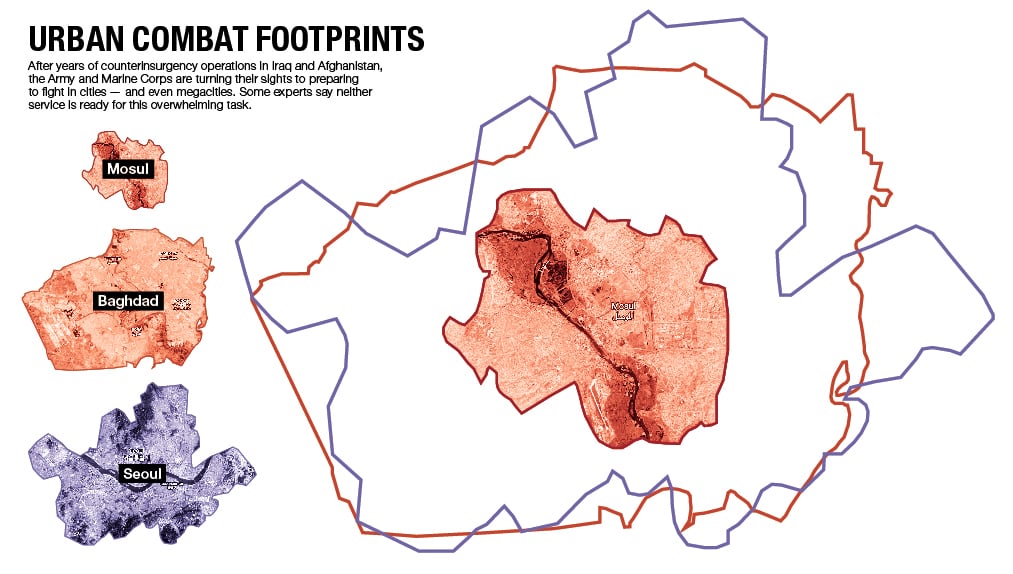

Those fights, while bloody, costly and destructive, hardly reach the scale of a megacity — Mosul is not equal to a neighborhood in Seoul, Milley has said.

In an urban fight, troops will have to move faster and more often, he said.

“If you stay stationary for any length of time, say more than a couple of hours, you are probably going to get killed.”

Long logistics trains won’t be available. And targeting must be more precise even than it is now.

“We can’t go out there and just slaughter people,” Milley said. “That’s not going to work.”

As for the Marines, Neller is pushing them back to ships and the littoral, or near-shore, contested area — and, effectively, closer to cities.

But, for most of the careers of those two men and their peers, attention on urban fighting has been sporadic or focused on lower level tactical work such as room clearing exercises.

Doctrine for urban fighting long consisted of avoiding cities at all costs or destroying everything in the path to defeat the enemy. Neither is a realistic option for U.S. forces in dense urban fighting.

Experts interviewed for this article roundly agreed that neither service is sufficiently prepared for operational or strategic-level urban combat.

Mark Bowden is the author of two deep studies of U.S. urban battles: “Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War” and “Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam.”

He believes that, if conducted properly and with buy-in from the public, those fights can be fought, if necessary.

“As a rule, if you’re going to commit the military to war somewhere in the world, you have to lay the groundwork,” Bowden said. “You have to be honest with people and explain why it’s necessary… that’s your best chance at building a more enduring public support.”

RELATED

Returning attention to the urban fight is not a new idea.

Retired Col. Russell Glenn now serves as the director for plans and policy, deputy chief of staff for the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command. In 1993, while on a temporary assignment to the RAND Corporation, he chose urban operations as a research topic. He was told there wasn’t much interest in that research.

Later that year, Army Rangers and Delta Force operators were caught in the bloody Battle of Mogadishu. Nineteen U.S. service members were killed and 73 wounded. The fight led to the withdrawal of U.S. and U.N. forces.

Then, people were interested.

Then-Marine Corps Commandant Gen. Charles Krulak unveiled his concept of the three-block war and the strategic corporal, which pushed decision making down to the lowest levels of the noncommissioned officer corps.

That thinking wasn’t far removed from Marine Lt. Gen. Ron Christmas’ experience in Hue, where he was awarded a Navy Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor, while a company commander.

“Once you go house to house, once you go room to room, it is a squad leader’s war,” Christmas said. “It’s up close and personal. …You see the guy you kill.”

Both the Army and Marines maintained that focus until a more pressing matter: the 9/11 attacks and subsequent responses, which drew resources into the combat operations that continue today.

Former Army Chief of Staff Gen. Ray Odierno directed urban operations be a focus area for his Strategic Studies Group in 2013. He had TRADOC make megacities part of its future study plan.

Soldiers with the Asymmetric Warfare Group have looked at how a brigade commander deals with an urban environment by reviewing urban operations from 1980 until 2016, as well as recent analysis of the Mosul battle.

Capt. Ernesto Amador, an AWG operational adviser, added that whatever the time frame or location, urban operations are “manpower intensive, time consuming and a lot of blood is spilled.”

Increased use of manpower and logistics has not changed. Marine veterans of the battle who contributed to a “lessons learned” study on Hue said they used 10 times the amount of ammunition fighting in the city as in the countryside.

Some key lessons AWG is pushing forward are ways to find a “common operating picture” across the battlefield so disparate units know what’s going on in real time, and training in analog methods for when soldiers find themselves in a degraded communications environment.

“I do think that evolution of tech and the role that tech plays cannot be downplayed. Changes the nature of the battlefield just by the way information flows,” said Maj. Christopher De Ruyter, AWG’s operations officer.

Emerging Technology

U.S. forces have long held a wide margin of technological superiority over their foes, from precision-guided weapons to sensor systems and drone surveillance capabilities.

Off-the-shelf technologies such as commercially available drones, bomb-making plans shared on the Internet and social media have given low-level, nonstate actors ways to disrupt U.S. technology.

Marine Brig. Gen. Robert Sofge, deputy commanding general of operations for Operation Inherent Resolve, told Army Times that enemy forces in Mosul adapted drones to drop 40mm grenades from above and used advanced vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices to deter Iraqi forces early in the fighting.

He also credited Islamic State fighters with running a sophisticated information operations mission.

Some Iraqi solutions were low-tech, such as bulldozers to clear pathways and leaflet drops along with TV announcements to reach the civilian population.

For some, the answer to urban complexities is more technology and data in the hands of U.S. troops.

Department of Defense research programs and industry partnerships are working with drone swarm technology, drone delivery to reduce logistics chains, increased electronic jamming of enemy sensors and networks, and pulling data from every corner of the battlefield into a digestible form.

RELATED

But there are varying views on technology’s role in urban combat.

As West wrote for The Atlantic last year, “Urban battle will remain a slugfest, with the basic ingredient remaining heavy doses of high explosives. No technology is emerging to replace that.”

Army Col. Douglas Winton has argued in his U.S. Army War College dissertation that urban combat does not substantially degrade the military capability of a superior force — so long as the superior force has sufficient political will and preparation.

There are steep learning curves, though, when a force is not prepared.

David Johnson, a retired Army colonel who is now a principal researcher for RAND, recounted interviews with a brigade commander in Baghdad who lost seven Strykers in seven days before moving Bradleys and M1 Abrams tanks into the fight.

Johnson said simple equipment considerations pay huge dividends in an urban fight. Tracked vehicles, while heavier than wheeled, produce less ground pressure, which is important on bridges.

Tracked vehicles can also make tighter turns in narrower urban lanes and don’t get stuck as easily as wheeled vehicles.

There also are some non-weapon tech tools that are already available and simply need to be applied.

Glenn advocates maintaining urban databases to watch the flow of a city and train data miners to regularly update data on key cities.

He noted in a 2016 article for Small Wars Journal that geo-profiling can track patterns of terrorist movement and attacks, and cell phone data was used to analyze and slow malaria outbreaks.

But those advances also bring with them their own challenges.

Glenn said the information needed to “feed what is sure to be a voracious intelligence beast” will take enormous amounts of manpower and resources.

RELATED

Changing the Force

Even in 2018, Army and Marine formations are organized and equipped for a rural rather than urban fight.

Milley advocated last year for building “small formations that are networked and can leverage Air Force and naval-delivered joint fires” to work in dense urban areas. They will likely be a company- or battalion-sized element, he said.

And new formations do take shape when the chief wants them. The Security Force Assistance Brigade is heading to Afghanistan this spring — Milley unveiled the SFAB concept in mid-2016.

Spencer, who also heads the Modern War Institute at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, wants to see more dedicated facilities and experts focused on urban fighting.

“We still do not have units that are even remotely prepared to operate in megacities,” Spencer said.

He noted that the Army has courses to deal with the desert, jungle and mountain terrains.

“Yet, despite conducting operations in cities for the past fourteen years, there is still no school for urban environments,” Spencer wrote in an article posted at the MWI’s Urban Warfare Project.

Spencer pushes for a Megacities Unit, a brigade combat team of 5,000 soldiers with three battalions of mobile infantry and one battalion each of the following: armor, fires, engineer, aviation, support, military intelligence, cyber electromagnetic activities, and explosive ordnance.

He sees the new unit as the “primary learning organization” for the Army and at the forefront of development of planning and doctrine for megacity fighting.

“If you don’t build experts, then you get no change,” Spencer said.

Some see other ways to get there.

Capt. Zachary Griffiths, a Special Forces officer and West Point instructor, wrote on the Urban Warfare Project that the Army should adopt urban combat leader courses in each division.

But where will they train?

There are urban training complexes at the National Training Center in Fort Irwin, California, the Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Polk, Louisiana, and the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Training Center at 29 Palms, California.

But the most advanced center in the United States, Spencer said, is the Indiana Army National Guard’s Muscatatuck Urban Training Center.

It is a 1,000-acre facility with 68 buildings, a reservoir, tunnel system and nine miles of roads.

But that still is not enough, Spencer said. Baghdad in 2003 was more complex and dense than the most advanced centers.

Despite the fits and starts of urban combat preparation, changes in doctrine and an increased focus from top leaders has some encouraged that actual transformation can occur.

“I think it’s beginning to happen,” Johnson said. “Gen. Milley has said in numerous forums, ‘this is the area the Army’s got to optimize for.’ That’s the tectonic movement if you will. The chief says it, it must be important.”

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.