Editor's note: This is the first in a three-part series on the Marine Corps' gender-integrated task force.

TWENTYNINE PALMS, CALIF. — It's a hot, dry desert morning in April. At Range 107, a Marine anti-armor team carrying individual 31-pound packs, a pair of 16-pound shoulder-launched multipurpose assault weapons, and four 13-pound rockets hikes up a rocky path into view.

In the four-woman team of a corporal and three sergeants, no member stands taller than 5five feet, four 4 inches. When they approach an 8eight-foot obstacle made out of a shipping container, it looms over them. But their movements are practiced.

READ PART 2: In gender study, discoveries but no decisions

READ PART 3: Experiment could create stronger force

Without wasting a motion, three Marines approach the wall and hunch down, allowing a teammate to scramble over them to the top. They then repeat the process with two women at the wall's base. Then one Marine boosts her teammate up. When the last Marine remains at the base of the wall, the three at the top lower down a stirrup made of three Marine Corps Martial Arts Program belts buckled into loops and linked together. The Marine at the wall settles her boot inside the belt contraption and gains a few feet on the vertical obstacle, reaching the waiting hands of her teammates, who pull her the rest of the way over.

The whole process takes just minutes. Then the Marines gather their weapons and push on, further up the hill, where the remainder of the day's tasks await.

At the Ground Combat Element Integrated Task Force — the only place to find an all-female anti-armor team in the Marine Corps — size matters, but so does ingenuity. The unit, which now includes roughly 200 male and 75 female volunteers distributed across a span of ground combat arms specialties, is winding down a period of combat assessments that began in early March.

Strapped with GPS and heart rate monitors and surrounded by research observers who record the speed and scope of each task into smartbooks, the volunteers live in a repetitive research cycle reminiscent of "Groundhog Day," a movie about a weatherman who kept reliving the same day.

Lance Cpl. Callahan Brown talks with a fellow Marine with the Ground Combat Element Integrated Task Force after an infantry assessment at Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms in Twentynine Palms, Calif., on Saturday, April 11, 2015. The GCEITF is evaluating the integration of female Marines into artillery, infantry and mechanized MOS's. (Mike Morones/Staff)

Photo Credit: Mike Morones

For infantry and weapons Marines, the task is to assault the same hill every two or three days, completing a specific set of physical and live-fire tasks over a span of a few kilometers. Special devices on their rifles capture every round's bullet impact to measure accuracy, while the heart rate monitors and surveys administered after each assessment capture individual physical exertion levels.

On alternating days, they hike nearly five miles 7 kilometers, or 4.5 miles, with their weapons and packs weighing just shy of 60 pounds, then spend two hours digging fighting holes that will later be filled back in with earth movers.

The goal of the task force is to develop gender-blind job-specific standards for each ground combat arms military occupational specialty that remains closed to female Marines. But there's a broader underlying question: Can female Marines do the job at all?

The Marine Corps' answer to that question is likely to be a nuanced one.

![chapter 1 female grunt teams [ID=27190129]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/embed.jpg)

Crafting the Marine Corps' first large-scale human research study was the task of Paul Johnson, a former Navy corpsman who now serves in Marine Corps Operational Test Evaluation Activity as a civilian. In a trailer complex that houses offices for the unit's headquarters element, Johnson quickly steers the conversation to size, a factor that continually asserts itself during the combat arms assessments.

In a practiced presentation, Johnson uses large and small smaller and larger dice to illustrate the difference between the average male and female Marines as they compose rifle squads and other units. A chart on the wall gets specific: The average male Marine weighs around 180 pounds, while the average female Marine is closer to 135. When it comes to hauling a wounded comrade buddy out of the combat zone — simulated in the assessment by Cpl. Carl, a dummy that who weighs 214 pounds fully loaded with gear — the heft can make a difference.

"But don't fall in love with the average," Johnson warns, noting that the Marine Corps has its share of smaller, slighter men and tall, muscular women.

Marines with the artillery section of the Ground Combat Element Integrated Task Force dig fighting positions in a timed assessment.

Photo Credit: Mike Morones/Staff

Certain apparent size-related challenges, such as installing female Marines driving as drivers in the Corps' decades-old light armored vehicles, designed for men between the to fit male Marines between the 5th and 95th percentile in height, proved not as daunting as expected. Early on, evaluating MCOTEA officials brought in shorter Marines to attempt the task and found they could do it without a problem.

Another concern for researchers was that of loading and repetition, and the delicate balance of ensuring daily tasks were challenging but not cycled in such a way that lack of recovery time would leave volunteers injured. During dry-run tests at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, where the task force trained for months before "deploying" to the the West Coast, researchers ruled out weeklong assessment cycles in favor of schedules that would give Marines a break every three to four days.

Guaranteed rest time isn't a luxury that Marines in combat zones, or even the Corps' infantry schools, can count on. But it made sense, Johnson said, given the months of assessments necessary to complete the study.

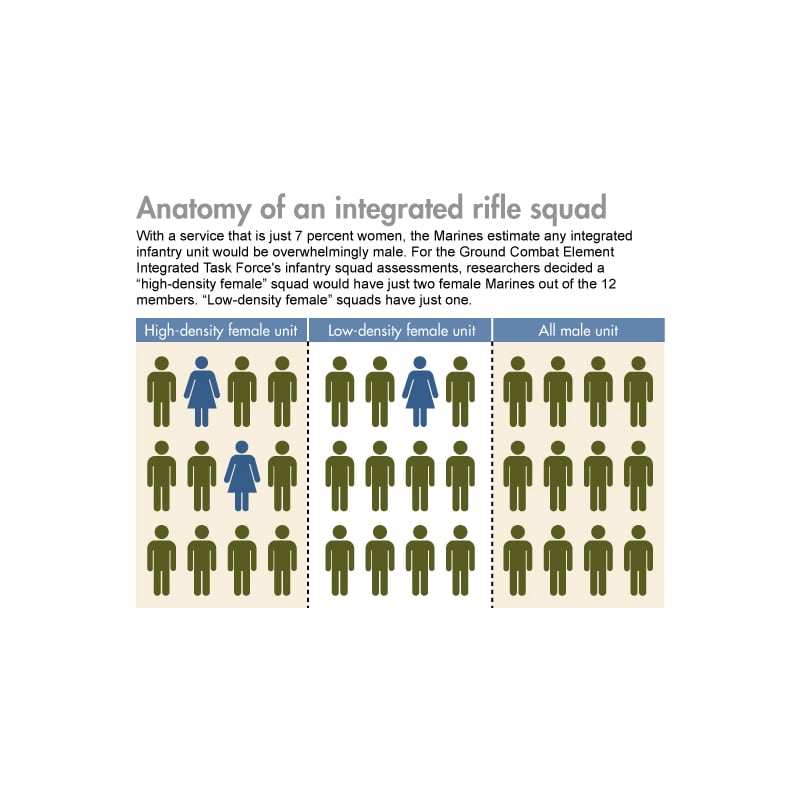

With a service that is just 7 percent women, the Marines estimate any integrated infantry unit would be overwhelmingly male. For the Ground Combat Element Integrated Task Force's infantry squad assessments, researchers decided a "high-density female" squad would have just two female Marines out of the 12 members. "Low-density female" squads have just one.

Photo Credit: Marine Corps

"Over the course of the experiment, an individual in the rifle squad will do about 140 kilometers, which is quite a bit," Johnson said. "We had to look at the total accumulated mileage ... to make sure that we were in a window that was sustainable."

For each new assessment, the MCOTEA staff assigned Marines their roles to Marines at random, populating three separate groups: all-male, low-density female and high-density female. Whether on a howitzer crew or rifle squad, the Marine volunteers then ran the day's tasks as observers logged speed, accuracy, exertion level and even the Marines' feelings at the end of the run.

But for a service Marine Corps that is just 7 seven percent women female between its officer and enlisted population, a "high-density female" team should match that ratio. does not mean mostly female. In the assessment, a high-density rifle squad has just two female Marines out of its 12 members. A low-density squad has just one.

"And so wWhen you do a probabilistic estimate of how likely you are to see a rifle squad that has a female in it or even two females in it, that's about as high as you're going to see, unless we dramatically increase the recruiting of females into the Marine Corps," Johnson said. "In theory you could create an all-female rifle squad, but one would really never come about through the manpower and assignment process, so you'd be spending a lot of money experimenting with something you'd probably never see in nature."

The tasks themselves are taken directly from the training and readiness manuals for each combat specialtyies, with an emphasis on repetitive tasks often-repeated jobs that require elements of physical exertion and teamwork. The six-Marine howitzer crews, for example, must set up their M777 155mm weapons and execute a series of challenging live-fire missions. Then individual crew members each shoulder a 105-pound howitzer round and carry it for two laps of 100 meters each. The mechanized crews, including LAVs, assault amphibious vehicles and tanks, do a day of live fire followed by a day of maintenance tasks, including changing a 175-pound tire and "evacuating" a fully loaded dummy from inside the vehicle to a recovery spot a set distance away.

"We didn't pick the sexiest [Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command]ARSOC standards for a task. What we tried to do is pick the core tasks that require a high physical component," Johnson said. "There are many cognitive tasks that these MOSs perform, but we're not studying cognitive aspects of individual Marines. In fact we hold an assumption going in that men and women cognitively are equivalent. And so we didn't spend our experimental resources looking at that."

Despite the emphasis on physicality, the experiment's designers welcomed creative workarounds that allowed female Marines to compensate for their smaller height and build.

During a maintenance tasks cycle at the LAV section, a three-Marine team changed one of the massive vehicle tires. Two men loosened the bolts from the front while a female Marine, Lance Cpl. Julia Carroll, lay prone underneath the vehicle, applying pressure to ease the tire off. When they re-fitted the LAV, a male Marine lay on his back and supported the tire with his leg muscles while Carroll and another Marine stood at either side to position it.

With these unwieldy vehicles, on which many parts outweigh the typical female Marine, a little ingenuity is necessary, said Lance Cpl. Brittany Dunklee, a 19-year-old volunteer from Gwinn, Michigan.

Early on in the assessment, Dunklee, a trained motor transport Marine, learned to manipulate the 175-pound tires by using another tire for leverage, to roll it up the treads and into place. Other Marines had their own tricks: standing on bench seats to open vehicle top hatches, compensating for shorter stature, and using leg strength instead of arm strength to apply extra force.

"I don't like to be told what I can't do, and this is one of those things," Dunklee said. "This paves the road for the rest of the females who want to do this."

For the all-female anti-armor team in Weapons Company, the belt loop device was born of necessity. The shortest member of the team is about 5 feet 1 inch tall 5'1 1/2", making the obstacle especially daunting.

Cpl. Janelle Lopez, 23, developed the technique with two lance corporals during an early trial run.

"Even though we might have the strength, sometimes our height does play a factor in some situations," she said. "So we tried it as a female team, and it works."

Cpl. Janelle Lopez, left, and Sgt. Maya Garnica conduct a safety brief before Marines with the Ground Combat Element Integrated Task Force participate in task assessments at Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms in Twentynine Palms, Calif., on Saturday, April 11, 2015. The GCEITF is evaluating the integration of female Marines into artillery, infantry and mechanized MOS's. (Mike Morones/Staff)

Photo Credit: Mike Morones

Not every workaround got the green light, however. Early on, the engineer platoon asked assessment staff about using breaching ladders or engineer tape, both internal assets for the unit, to get over the 8-foot wall.

"They told us, 'You may not always have those things with you,'" said 1st Lt. Stephanie Damren, platoon commander for the unit.

Col. Michael Samarov, Marine Corps force innovation office plans officer, said acceptable creative solutions had to embrace the spirit of the challenge.

"We expected that there would be ingenious solution and adaptation as Marines learned the problem; that's why all of these things were team tasks," he told Marine Corps Times in an interview at Quantico, Virginia. "For the wall obstacle, you could defeat it by going around it. That would not be an appropriate adaptation. In the end, it's who accomplishes the mission."

Volunteers were quick to point out, too, that mechanical aids only take you so far.

"It comes down to the pack," said Sgt. Kelly Brown, an infantry volunteer. "It's not like anybody's going to be able to carry it for you, so you're on your own."

The most significant way female Marines' slight stature and smaller, lighter frames present concerns for task force researchers regarding the injuries they may be more likely to sustain.

Task force and Pentagon officials have carefully guarded early data from the unit and declined to provide specialty-specific information about Marines who had been dropped due to injuries. But patterns are emerging, according to sources connected with the task force.

As of mid-April, the number of male volunteers had dropped from about 300 to 200, sources said, and the number of female volunteers was down from about 100 to 75. Because this is a human research experiment, Marine volunteers are allowed to drop on request from the unit for any reason. Those requests hese DORs are included in the total drops.

While most male volunteers have dropped due to non-injury related reasons, most female volunteers have been dropped due to injuries.

And the injuries do follow intuitive patterns. Staff with the task force's artillery element, in which Marines do not carry a combat load and operate in brief, intense bursts of effort, said they saw had seen only a few men and woman drop drops among male and female volunteers. Female drops due to injury had largely been the result of pre-existing physical issues, and knee and ankle injuries were the most common, said Capt. Andrew Miller, commander of Alpha Battery.

Injuries were more prevalent in the unit's infantry and weapons companies, where Marines carry between 30 and 60 pounds daily in addition to their weapons.

Even some of those who remained in the unit were recovering from knee and hip strain.

"I was on light duty for basically three cycles because of a hip injury that I received. I'm actually just coming back now, and it's been a struggle for me," said Lopez, the anti-armor team member. "[The sergeants with the unit are] understanding of my situation, and they push me when they know that I know my limits as well. It hasn't been easy but I'm thankful that I'm here."

All injuries are closely monitored and treated by the unit's medical staff, said task force officials. Samarov, the innovation plans officer, said certain controls were in place to make sure no element of the task force dropped too many Marines. If unit drops fell below a certain level for any specialty, he said, the research would have to be curtailed for lack of an adequate sample size. So far, that hasn't happened, he said.

Cpl. Allison DeVries talks with Pvt. Alec Hettinger, a data recorder, following an artillery assessment. The staff records everything from accuracy and speed to a Marine's feelings following an exercise.

Photo Credit: Mike Morones/Staff

Still, there are data points related to the physical toll on female Marines' bodies that will remain elusive, even after task force research concludes.

"Anything that requires a long period of time to know is very difficult to identify inside a relatively fixed study, even a long study like this one," said Samarov said. "So we know, for example, that a 20-year career as an infantry Marine takes a toll on you. There's no way we can identify what female Marines in combat arms, what the toll of a 20-year career would be on their bodies. Would it be the same as their male counterparts?"

Task force Marines are now concluding the 29 Palms assessment here and traveling to Mountain Warfare Training Center Bridgeport, Calif. and Camp Pendleton, California, to begin a set of geography-specific tasks. Infantry Marines and combat engineers will participate in mountain warfare assessments at Bridgeport, while some of the mechanized units will perform amphibious landings at Pendleton.

The assessments will wrap up in mid-July, when all task force Marines are due back to Camp Lejeune to regroup for a final time.

Paul Johnson, the experiment's principal investigator, will then have several months to prepare a detailed report on the unit's findings, which will be send to the commandant this fall.

UP NEXT WEEK: A perspective develops — can female Marines get the job done?