ATLANTA – Gen. Robert Neller was speaking with California-based Marines shortly after becoming commandant when he got a tough question from a noncommissioned officer.

The sergeant, who deployed three times, told him that his comrades made it home from the warzone only to later take their own lives. "What are you doing about that?" the NCO asked.

Commandant Gen. Robert Neller speaks at an American Psychiatric Association conference in Atlanta on May 17. Neller participated in a panel discussion and asked for more collaboration with the psychiatric community to help Marines and veterans.

Photo Credit: Staff Sgt. Gabriela Garcia/Marine Corps

One of his first steps involved exactly what he's asking Marines to do – asking for help.

Neller recently spoke here during the American Psychiatric Association's 169th annual meeting. He invited Marine Corps Times to attend the engagement, where some of the country's top mental health experts gathered for a five-day conference. Neller wants their help in fixing what he sees as one of the Corps' biggest challenges: saving Marines from themselves.

A new survey of 3,000 post-9/11 veterans found that 40 percent of respondents considered suicide at least once after they joined the military. Four out of five of those polled said troops dealing with mental health issues don't get the care they need — while they're in the military or once they're out.

Neller said he is also troubled by the spike in suicides for Marines who've never deployed. That number has jumped from 36 percent of the service's suicides in 2013 to 66 percent in 2015. During the first four months of this year, that number is up to 73 percent. Sixteen Marines who never deployed have taken their own lives in 2016.

"We can't afford to lose a single Marine to anything, whether it be accident, injury or suicide," Neller said. "I can tell you — giving my solemn word — that the Marine Corps will try to help anyone who comes forward."

One of the biggest myths that Neller is out to crush is that asking for help will harm a Marine's career. Whether it's combat-related post-traumatic stress, relationship troubles or other stressors, Neller said it's time for Marines to start talking about what's on their minds.

It’s not the first time the commandant has vowed to protect the careers or of those struggling. He once came to the aid of a Marine reservist who had just been selected for command, but was dealing with some mental health issues following a stressful assignment.

Psychologists say that if one Marine commits suicide, it has a ripple effect among the entire unit, which could put others at risk.

Photo Credit: Cpl. Sarah Cherry/Marine Corps

"He had to do [this] 25 times: go to somebody's house and tell them that their son or daughter was dead," Neller said. "It crushed him."

The Marine knew that if he turned down the command assignment, his career would essentially be over because he'd never get that chance again.

"He said: 'I can't go to command. I'm not ready. It's not fair to the Marines. I'm still working through this.'" Neller said. "…So I called the guy that was running Manpower, who was a friend of mine. I said, 'Look, he can't do this. You gotta take him off the list and make sure he gets to compete again.' And they did."

That's not typical of every Marine's situation though. One woman in the audience here shared a story about her friend, a retired Marine major. He was a pilot with a drinking problem, but he didn't ask for help for fear that he would be grounded.

He went into retirement an alcoholic, she said, and eventually drank himself to death.

"The fact is," Neller responded, "if he had come forward and said he needed help, he would have been able to fly after he completed his treatment."

Staff Sgt. Ryan Culberson, a joint terminal attack controller, understands why Marines are hesitant to seek help. After five combat deployments, he sought treatment for post-traumatic stress — but it wasn't easy.

Marines are used to dealing with physical wounds, he said. Those can be seen and more easily fixed. But mental injuries aren't something most Marines talk about.

"I was always worried to bring my issues up fearing that I would get treated differently by my fellow Marines," Culberson said. "Admitting you have a problem shows that you may have a weakness."

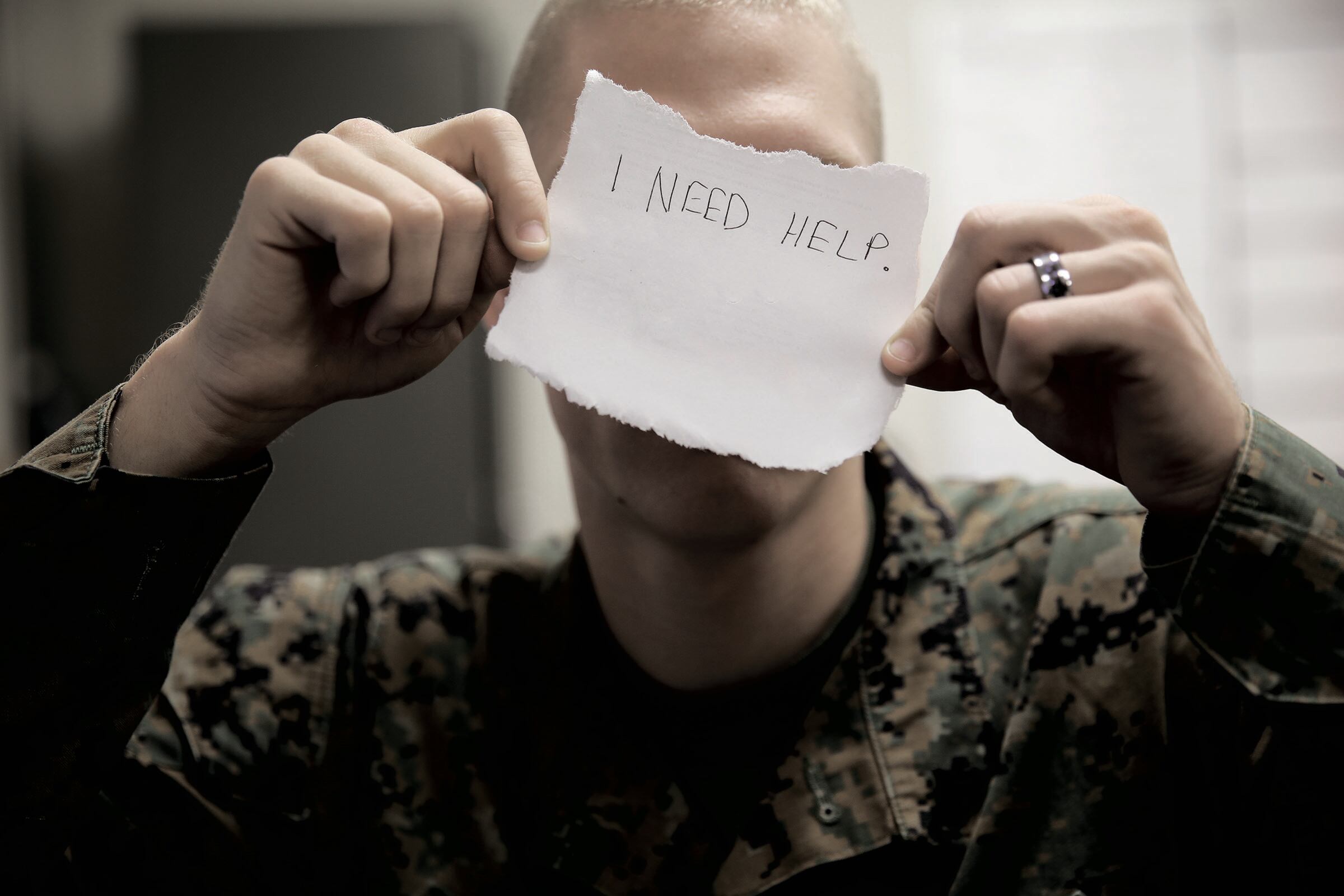

More Marines who have never seen combat are taking their own lives compared to years past.

Photo Credit: Cpl. Russell Midori/Marine Corps

Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps Ronald Green said that Marines need to understand that seeking help is a sign of strength — one that can actually save their careers. "What will end your career faster is not asking for help," he said.

Society in general is reluctant to talk about mental health issues, Green added, and Marines bring that mindset with them when they join the service. As a result, they may feel too embarrassed to ask for help, or fear it will negatively affect their career.

Neller acknowledged that some Marines have endured retaliation after they sought help with PTS and other mental health injuries. "I'm not going to sit here and tell you that it hasn't happened because I've heard about it myself," he told Marine Corps Times.

If a Marine feels they're being punished for asking for help, Neller said they should feel empowered to raise the issue with their chain of command. Nothing should stop them from getting the help they need.

Since the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, there has been a lot of focus on post-war challenges. Many thought that taking care of war vets would reduce the number of suicides across the military.

But the Marine Corps’ recent suicide data has uncovered a new and distressing trend: Most of the Marines who’ve taken their lives over the past three years have never seen combat.

Neller is committed to finding out what's behind that, but it isn't easy. The situations that lead to suicidal tendencies tend to be varied and complex.

"There is no silver needle in the haystack," Neller said. "Is it physical fitness? Is it their intelligence level? Is it their relationship? Is it money? Is it shame? Is it pride?

"Yes," he said. "It's everything."

Marines with 2nd Assault Amphibious Battalion run together during a R.A.C.E for Suicide Awareness event at Camp Lejeune, N.C. The Corps' leaders are working to end the stigma that seeking help for mental health issues will harm Marines' careers.

Photo Credit: Lance Cpl. Krista James/Marine Corps

The Corps has a long way to go when it comes to helping Marines who've never been to combat, said Maximilian Uriarte, author of the popular Terminal Lance cartoon and the graphic novel, "The White Donkey." Marines face a lot of mental health issues in garrison, he said. Some of his junior Marines who never deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan tried to kill themselves.

Those Marines are often stigmatized if they ask for help, though, Uriarte said.

"I don't think the Marine Corps itself has much patience for mental health issues that are non-combat related," he said. "…These events are very looked down upon amongst most Marines as being weak-willed."

Marines who've never been to war commit suicide for a lot of the same reasons civilians do: They are dealing with relationship issues and other psychological problems that they feel cannot be solved, said Craig Bryan, a psychologist and executive director of the National Center for Veterans Studies at the University of Utah.

Green said another societal issue that affects the Marine Corps is addiction. Marines who are injured while deployed or in training can develop a dependence on opioids. Or those in legal or financial trouble sometimes feel like there's no other way out.

"We're trying to tell them, 'There is another way out — this is not the end of the line,'" he said. "You're not measured by how far you fall, but how far you get up."

But there's something else unique to communities like the Marine Corps, Bryan said. While camaraderie in all of the military services is strong, suicides in the Marine Corps hit particularly hard — and that can cause a ripple effect across a unit.

"There's a certain subgroup of Marines who might then look at that other Marine's death and say: 'Well, if he can't handle it, how am I going to possibly handle it because I really respected him; I valued him; he's a really great guy. If he can't take it, what does that say about me?'" Bryan said.

Studies have shown that when a student in middle or high school commits suicide, the risk for that person's classmates killing themselves goes up, said Dr. William Nash, director of psychological health for the Marine Corps.

"Seeing someone else do it, hearing about someone else do it, makes it easier for anyone to entertain the thought," he said.

The phenomenon is called "contagion," and the Marine Corps hopes to study whether suicide clusters exist in Marine units, he said.

When Marines are still in uniform, leaders have an obligation to take care of their troops, Neller said. It's up to them to make sure Marines' injuries are treated before they get any worse — whether it's a knee problem or PTS.

"Leaders have a responsibility to ensure that Marines don't get seriously injured because we need every Marine," Neller said. "Every Marine is important."

Bob Pruitt speaks with a Marine before the start of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines "Dark Horse" reunion in April. The commandant and sergeant major of the Marine Corps are encouraging more leaders to hold reunions to help keep Marines connected.

Photo Credit: Lance Cpl. Shellie Hall/Marine Corps

It can be a challenge to identify mental injuries, though, especially if a Marine is trying to hide it. Culberson, the JTAC, said being a good mentor can go a long way — especially in a culture that prides itself on its warrior mentality.

"Being approachable is a key to having Marines feel like they can trust you have their best interests in mind," he said. That will make it more likely that Marines will open up to you if they're struggling.

That's where the sense of camaraderie and group think in the Marine Corps can be incredibly powerful, said Jackie Maffucci, a research director at Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. That organization's survey of the 3,000 Iraq and Afghanistan vets found that troops are likely to seek help if someone recommends it.

"That really demonstrates the power of community, of peers, of family," she said. "…It's very important to have those individuals in your life who are saying, 'Hey, I really think it's time you did something about this.'"

Once Marines hang up their uniforms, though, that is much harder to do. Each year, about 30,000 Marines transition to civilian life — and "they're still our responsibility," Neller said.

"This isn't just about post-traumatic stress," he said. "This is about the loss of cohesion, survivor's guilt, disorientation, missing your friends, wanting it to be the way it was — but it will never be that way again."

In the past, those transitioning would turn to Veterans of Foreign Wars or American Legion facilities and share their war stories, he said. This generation of veterans isn't as interested in joining those organizations though. Culberson said he's tried to hit the local VFW, but there's a big age gap between him and other members, and it's not always a welcoming environment.

Veteran Cpl. Ryan Provasi accepts a challenge coin from Col. Jason Morris at the the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines reunion in April. Commandant Gen. Robert Neller cited that reunion as a success story on how Iraq and Afghanistan vets can stay in touch.

Photo Credit: Lance Cpl. Shellie Hall/Marine Corps

That's why Neller and Green are encouraging Marine units to schedule more reunions. Neller cited the reunion held in April for members of 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines as a major success story. By getting back together, members of that unit — which lost 25 Marines during a 2011 deployment to Afghanistan — are able to relive the camaraderie they experienced while on active duty, he said.

"Other units have been in tough fights and they've come back and they've had a significant number of Marines take their lives," Neller said. "This battalion has had two [suicides]."

Reunions are similar to rituals other warrior cultures have held throughout history, Neller said.

"The old men tell their stories of war — the young warriors listen and they learn and they get ready mentally for what they're going to face," he said. "History teaches us a lot of things."

Gina Harkins contributed to this report.

If you or someone you know is struggling, the Marine Corps DSTRESS anonymous phone and chat service is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week at 1-877-476-7734.