The Marine reconnaissance community has a storied history dating back the Corps’ first operational small boat units in World War II.

Its lore has captivated the ambitions of many young Marines wishing to earn the 0321-occupation specialty.

Recon Marines are tasked with land and amphibious reconnaissance, intelligence collection, surveillance and small unit raids, and straddle the line between special operations forces and conventional forces.

“I did infantry for my first four years, then I got bored with it,” said Marine Shawn Talbert, training cell chief with 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion in Okinawa, Japan. “It kind of felt like it was almost a dead end. And so I went to recon where there are no dead ends. It’s all rabbit holes in every different field.”

RELATED

But there may be some a dead ends in sight.

These elite Marines are on track for a manpower crisis; one that questions the Corps’ ability to sustain its reconnaissance force into the future at a time of rapid modernization across the force and as recon questions its mission.

Recent data is the truest teller.

“Manpower and Reserve Affairs identified the 0321 MOS [Military Occupational Specialty] as having the most inverted grade pyramid, specifically in the E-3 to E-4 ranks, which is having a significant effect on promotion timing,” Marine Corps Combat Development Command told Marine Corps Times.

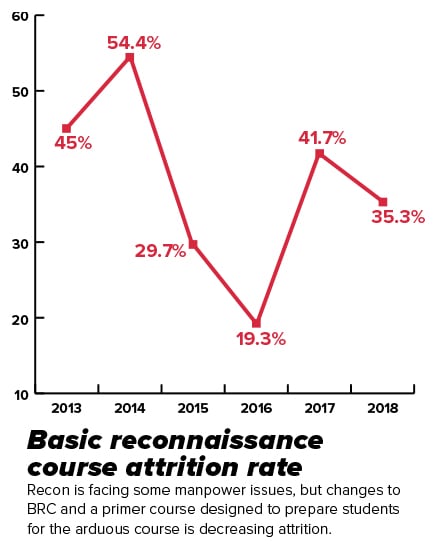

That issue is compounded by high attrition rates at the recon community’s 12-week rigorous Basic Reconnaissance Course, or BRC.

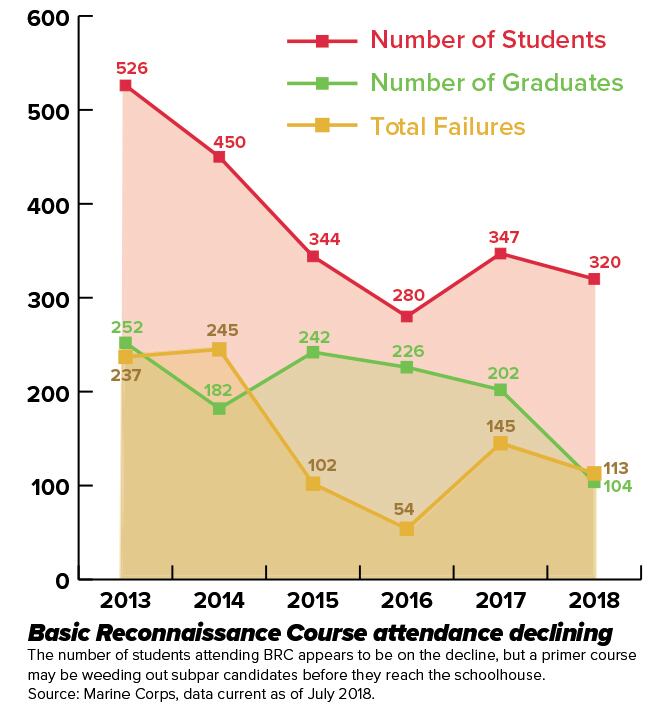

Attrition rates have been as high as 54 percent (in fiscal year 2014) are coupled with attendance rates that appear to be declining, according to data obtained by Marine Corps Times through a Freedom of Information Act request spanning the past five years.

Over those five years, BRC’s attendance rate saw a high of 526 Marines in 2013 and a low of 280 Marines in 2016 — a nearly 45 percent drop.

Former and current reconnaissance Marines who spoke to Marine Corps Times on condition of anonymity said the low numbers were disappointing and raised alarms about the community’s sustainability.

WHERE’S THE WARRIOR SPIRIT?

But manpower concerns are not the only issues facing the Corps’ elite and storied recon units.

Many former and current recon Marines have long complained about gear, morale and an overall feeling that their skillsets have been underutilized, especially over the course of America’s counterinsurgency wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

What truly is recon’s mission in the post-9/11 era and in the age of Marine Special Operations Command?

A common comparison told to Marine Corps Times by several members of the community, to describe recon’s search for an identity in the new era, is the HBO miniseries “Generation Kill,” which details the exploits of 1st Marine Reconnaissance Battalion as it barrels through Iraq during the opening of the U.S. invasion.

“The point, lance corporal, we’re supposed to be a recon unit of pure warrior spirit,” Sgt. Brad Colbert, played by Alexander Skarsgård, says in the show.

“We’re out here, 40 klicks in enemy lines, and this man of God here, he’s a f*ckin’ POG. In fact, he’s an officer POG. That’s one more layer of bureaucracy and unnecessary logistics, one more a**hole we need to supply MREs and baby wipes for.”

The scene depicts the frustrations of a community that often sees itself misused and misunderstood by the Corps.

Driving in armored trucks and carrying out missions generally the purview of infantry units is not what recon is trained to do.

“The ‘recon’ part is always just fairy dusted,” a former member of the recon and sniper community said.

“Recon isn’t the grunts; recon is special. The things in our T&R manual [training and readiness] are special operations missions. Yet, we basically have to use the same gear as the infantry.”

Since the creation of MARSOC, there also has been “somewhat of a competition of manpower,” between the two pools of prospects, a former reconnaissance company platoon commander told Marine Corps Times in 2017. “Marines have to make a choice.”

Both communities tend to draw the same type of Marine: “You get smarter, stronger, more of the Alpha-male type figures,” Talbert said.

But, as far as changing and learning new skills goes: “Reconnaissance has stayed pretty much the same for the past 20 years or more,” the former company platoon commander said, where MARSOC has developed several new skillsets.

And there are other signs of stresses.

Take for instance that this year the Marine Corps deployed reserve members of 3rd and 4th Force Reconnaissance Companies to augment 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion in Okinawa, Japan, as part of a Unit Deployment Program, or UDP.

Units who participate in a UDP usually conduct training on Okinawa, Japan, or with the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit.

It’s not entirely uncommon for reserve units to be called up to conduct a UDP, but sometimes it’s to pick up slack for active-duty units that are otherwise busy.

Reserve Marines with 2nd Battalion, 23rd Marine Regiment are deploying on a UDP to Okinawa in October, taking the place of Camp Pendleton, Marines with 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division.

The 5th Marine Regiment was simply retasked with evaluating and testing the Corps’ new Joint Light Tactical Vehicle, which is set to replace the Marine Corps’ aging fleet of Humvees.

“As the Marine Corps strives to make the most of its modernization plans, every opportunity will be taken to improve the capability and readiness of our forces at the same time,” Lt. Col. Ted Wong, a Marine spokesman, told Marine Corps Times about 2nd Battalion, 23rd Marine Regiment’s UDP in June.

It’s the first time in several years a reserve unit has been called up to take on a UDP.

But, while the reserve force recon companies are augmenting the UDP, their deployment is a little different than the battalion level UDPs, according to Maj. Roger Hollenbeck, spokesman for Marine Forces Reserve.

The reserve force recon Marines in Okinawa eventually will be relieved by another reserve platoon of recon Marines “in order to provide continuous support to the active duty battalion on Okinawa,” Hollenbeck said.

FINDING A SOLUTION

But the Corps is working hard to find a solution.

At the end of September, the Marine Corps kicked off its first extensive rank structure review in nearly 20 years to look at manpower issues as a result of the Corps’ push to modernize, known as the Marine Force 2025 concept, according to a forcewide message.

A review by Manpower and Reserve Affairs identified 42 job fields that range from recon, intelligence, aviation and logistics that are suffering from an inverted grade pyramid, MCCDC said.

Inverted grade pyramids can stymie and logjam promotions and result in a diminished pool of lower rank-and-file Marines in a various job. It can also create future manning challenges.

The Corps has highlighted the recon field as a priority.

Specifically, Manpower and Reserve Affairs found that the E-4 population was higher than the E-3s in the 0321 community. This means there are more corporals or noncommissioned officers in the recon field than junior enlisted folks.

Which could be a big problem in the long run.

Plus, recon’s “independent operator, independent thinker” model puts “a lot of responsibility on even the youngest lance corporal or corporal,” said Talbert.

“The information that they need to know and the mindset that they need to have is probably equivalent to a sergeant in the infantry.”

Marine officials say they are not sure what has caused the inverted grade structure in the 0321 community but are currently reviewing the issue.

But not all is doom and gloom.

MCCDC told Marine Corps Times that the recon community met its fiscal year 2018 recruiting goal and 99 percent of its retention goal.

Some of that may be the result of big bucks the Corps dished out as part of its Selective Retention Bonuses for fiscal years 2018 and 2019.

A sergeant moving into the recon field could net a $50,000 bonus on top of a 72-month lateral kicker of $40,000, netting a future recon Marine $90,000.

And gunnys and above with 10-14 years of active service rate nearly $30,000 for reenlisting as an 0321.

“The current inventory of recon Marines is sufficient to fill almost 90 percent of the required billets across the USMC,” said spokeswoman Capt. Karoline Foote.

And changes are afoot to address its various challenges to include attrition, graduation and attendance rates.

From fiscal years 2013-2018, the highest attrition rate at BRC was 54 percent, which is high, but doesn’t quite match the scout sniper school attrition rate of nearly 67 percent in 2014, which has since dropped below 50 percent.

The Corps’ elite recon and sniper schools are arduous and physically demanding. Relatively high attrition rates are expected as these schools seek to evaluate the best and toughest among a small pool of candidates.

But attendance at BRC also appears to be on the decline and has not peaked above 400 candidates since 2014, according to data obtained by Marine Corps Times.

To address these challenges, Training and Education Command recently kicked off a Reconnaissance Training Management Team Working Group,” which "identified gaps” in recon training, Foote said.

As a result of the working group, BRC will now have 11 additional days of instruction. The Corps also decided to update its recon prescreening course known as the Basic Reconnaissance Primer Course, or BRPC, which is relatively new.

“Using historical data and feedback, the new BRPC continues to provide much needed training in aquatics and physical conditioning. It will now include Land Navigation to allow for increased remediation and written test opportunities to better prepare Marines for the cognitive aspects of memorization and written exams throughout BRC,” Foote explained.

Some former and current recon Marines posit the decline in attendance at BRC may be a result of the primer course weeding out students who otherwise would not have graduated BRC.

And Corps officials said since the new screening course and changes to BRC went into effect graduation rates have soared to nearly 80 percent.

“The vast majority of attrition from the Basic Reconnaissance training program result from failures to pass initial screening,” Foote explained. “Once candidates are screened to meet the medical, cognitive, and physical requirements to conduct high risk training, the attrition rate is low.”