A chance encounter with a Marine security guard at a U.S. embassy drove young boy Sam Farran to later enlist in the Marine Corps on an open contract on Nov. 2, 1978.

The Lebanese-born, U.S.-raised Marine later transitioned to the Marine Corps Reserves, but his Arabic-speaking background led to an assignment helping translate during the Persian Gulf War and later a job with the Defense Intelligence Agency and private security work across the Middle East during the height of regional turmoil.

Those events led to Farran, 61, being taken hostage by Shiite Houthi rebels in 2015 and held for six months in a 5-by-12-foot cell. His training helped him survive but he knew at any moment a single bullet could end his life.

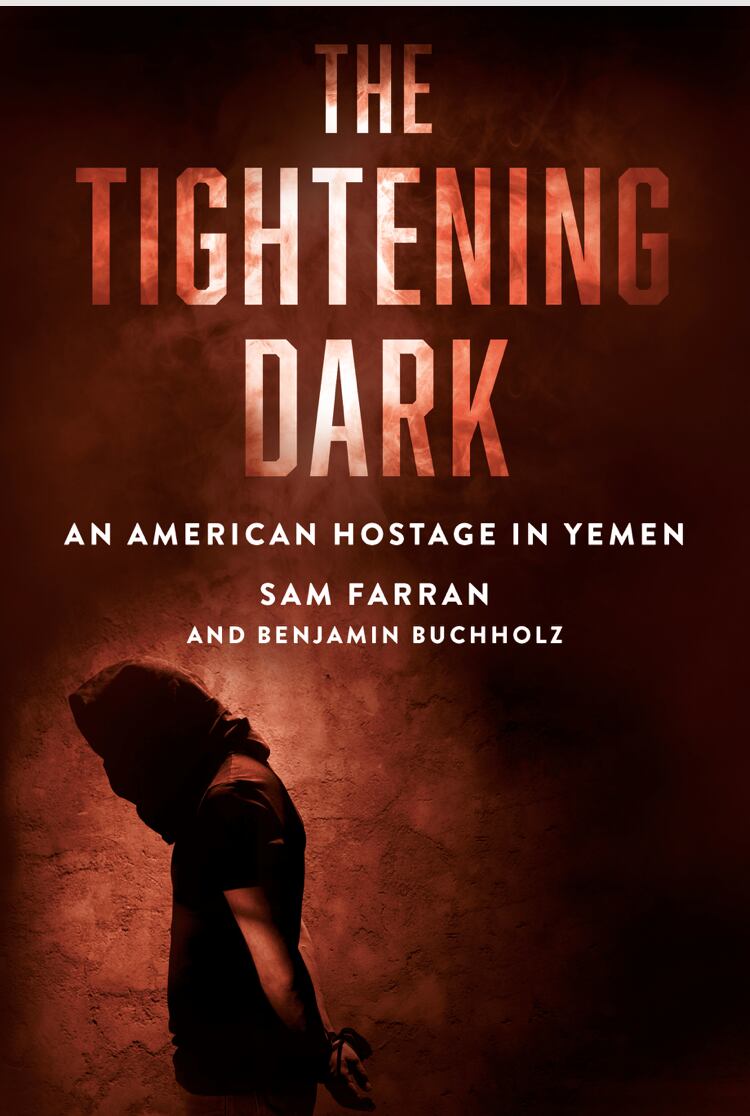

Farran collected experiences throughout his life to share his story, as an Arab-American, Muslim Marine who’d weathered the life of a hostage and lived in the book “Tightening Dark,” which he co-authored with Benjamin Buchholz, former U.S. defense attaché in Yemen, in 2021.

The retired Marine warrant officer spoke with Marine Corps Times about his time in the Corps, his time as a hostage and what he’s learned in the process.

Editor’s note: The following author Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: Can you tell readers why you joined the Marine Corps?

A: I was born in Lebanon but in 1968 my family moved to Libya. It was there, at the U.S. Embassy in Tripoli, Libya, where I first saw a Marine in uniform.

He was dressed in an immaculate, deep blue uniform with red stripes on the legs as well as medals and insignia everywhere on his chest and along his high, starched collar.

This man held a rifle over one shoulder, smartly and confidently, and he squared his corners, turning at right angles, sharp in all his movements as he stepped into position beside the doorway, there to bring the rifle’s buttstock crashing down beside his foot before he seemed to freeze in place, standing their statute still. It was something aspirational.

I started talking to recruiters when attending Fordson High School in Dearborn, Michigan. Over my mother’s protests I enlisted on three-year open contract my senior year. My parents were skeptical but when I came home my dad took me everywhere, insisting I wear my uniform.

Q: What did you do in the Marines?

A: I served as an engineer for my first, active-duty enlistment then I joined the Marine Corps Reserve near home in Michigan after finishing my active-duty time.

I had taken a language test for Arabic when on active duty, but the proctor thought I cheated. I was offended that he didn’t trust that I knew the language well enough not to cheat, so I didn’t pursue that track.

But when the Persian Gulf War kicked off, the Corps needed Arabic speakers, so I was pulled to work on interrogator/translator assignments with the Defense Intelligence Agency.

After the war I saw a job advertisement in a Marine Corps Reserve magazine and applied. As a warrant officer I was the most junior rank in my defense attaché class, which threw the joint military instructors and staff since the rest were all commissioned officers.

I worked doing training for partner nations in the Middle East after 9/11. And I continued for more than a decade with the Corps and DIA doing that work before retiring from the Marine Corps in 2008.

Q: What did you do after your time in the Corps?

A: After serving as a defense attaché, mostly in the Middle East, I worked as an analyst and facilitator for U.S. and foreign companies need of security consultation in the region.

Q: The book covers this in detail but what can you tell readers here about your time as a hostage and any lessons you learned?

A: On March 27, 2015, about a dozen armed Houthi rebels in official uniforms, part of a unit a counterterrorism unit the United States helped create to fight al-Qaida, stormed the building where I stayed.

They confiscated electronics and handcuffed me and Scott Darden, another American working in Yemen. Over the next six months I endured beatings, taunting and interrogations.

Imagine the irony, I’d been kidnapped by members of the Yemeni National Security Bureau, which I helped create.

At times, the situation and my thinking turned dark. They’ve got nothing to lose. They don’t have to report to anyone. They don’t have to affirm anything. I could just disappear. They’re going to do it. They’re going to shoot me right here, in this room, and it’ll all be over.

But eventually, I was freed and came home to my family.

Many Marines don’t get the training that I did, working in intelligence and serving as a defense attaché.

When Marines or anyone decide to get into this field, intelligence or special operations, I advise them to concentrate, to take their training very serious.

You might think ‘what are the chances of this really happening?’ They are 0.0001% chance, but believe me, I happened to be that 0.0001%.

It is particularly good training. I would advise that young lance corporal to not let what happened to me deter them. You just must go out there, take your chances, play it smart, take the countermeasures you are taught, which I did. But you get to a point where sometimes it’s out of your hands. You do everything you can.

Q: Another Marine veteran, Austin Tice, was taken hostage in Syria in 2012 while working as a journalist. Have you followed his story?

A: I’m familiar with the situation ― mostly what has been written about by media. His situation is terribly similar to mine, except going as a reporter to Syria and I was in Yemen.

I just cannot imagine what I went through in six months he is going through right now for 10 years. It is heartbreaking, it is just heartbreaking.

I’ve read about the failed attempts to get him out. Unfortunately, when the state department is playing a role, when the politics overcome the individual, it is sad to see those who are left behind.

RELATED

I take it personally and I tried to contact the family to see if there is a way that I can help. My release was conducted through a third country, Oman, and that was negotiated and that was what got me out.

Our government knew about it, coordinated it, but we had a third party that was involved able to get me out. There’s always sources out there that have these back channels, to get these deals done to get them out.

Q: What would you hope that Marines who read this book might take away from the experience?

A: I would like the Marines to get one thing and one thing out of it: The dedication that we put into ourselves and into the country, it’s not a waste. What we do is important, not only to our nation but to the entire world.

Everybody knows the No. 1 force in the world is the U.S. Marines. I would like them to understand their reputation around the world is very well-known and that is because of our dedication, our training and our purpose in this country to serve honorably, with dignity and integrity.

It’s always interesting when they ask me, being a Muslim immigrant in the Marine Corps. Mind you, I enlisted in 1978 and then in 1979 the American embassy was taken over in Tehran.

At that time, people in the United States can’t tell Farsi from Arabic, just that a Muslim is a Muslim. It was very difficult to be called by ignorant people a “raghead.”

But one thing I learned in the Marine Corps ― I’m not going to say the Marine Corps is 100% prejudice free, because it is not. But one thing I learned back then was the Marine Corps is one Marine Corps ― the green machine.

Despite the difficulties you go through at the end of the day, you know, what they always say, a bad day in the Marine Corps is better than any day outside.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.