The Army redesignated Fort Polk, Louisiana, as Fort Johnson on June 13, concluding a move made in accordance with a 2021 policy that requires the removal of names that commemorate the Confederacy from Defense Department properties.

Fort Johnson, one of nine Army installations to receive a new moniker under the Pentagon’s Naming Commission, was selected to honor New York National Guard Sgt. William Henry Johnson, a Black World War I soldier whose frontline heroism in France would etch his name into the history books as a lionheart of the famed Harlem Hellfighters.

Johnson was a mid−20s railway porter in Albany, New York, when he enlisted in the Army. It was June 1917. Congress had declared war against Germany just two months prior and Johnson was eager to join the fight.

Standing at only 5-foot−4 and 130 pounds, Johnson took the oath of enlistment in Brooklyn and was subsequently assigned to C Company of the 15th New York Infantry Regiment, an all-Black National Guard outfit that would later become the 369th Infantry Regiment — also known as the Hellfighters.

The 369th became the first Black combat regiment to serve with American Expeditionary Forces. Prior to the unit’s formation, Black soldiers who wanted to serve in combat were forced to work around U.S. military restrictions by way of enlistments with the French or Canadian armies.

Racism encountered by Black soldiers at the time was severe. U.S. Gen. John G. Pershing even went as far as authorizing the distribution of a pamphlet, titled “Secret Information Concerning Black American Troops,” advising America’s French allies against relying on — or even associating with — their Black counterparts. In his correspondence, Pershing claimed the men of the 369th were “inferior” to white soldiers, acted as a “constant menace to the American” and didn’t possess a “civic and professional conscience.”

Burdened by a misguided reputation, Johnson’s unit was initially relegated to labor-intensive duties. That was until they were ordered into battle in 1918 and assigned to the French Army, who seemed to care far less about race than their American allies.

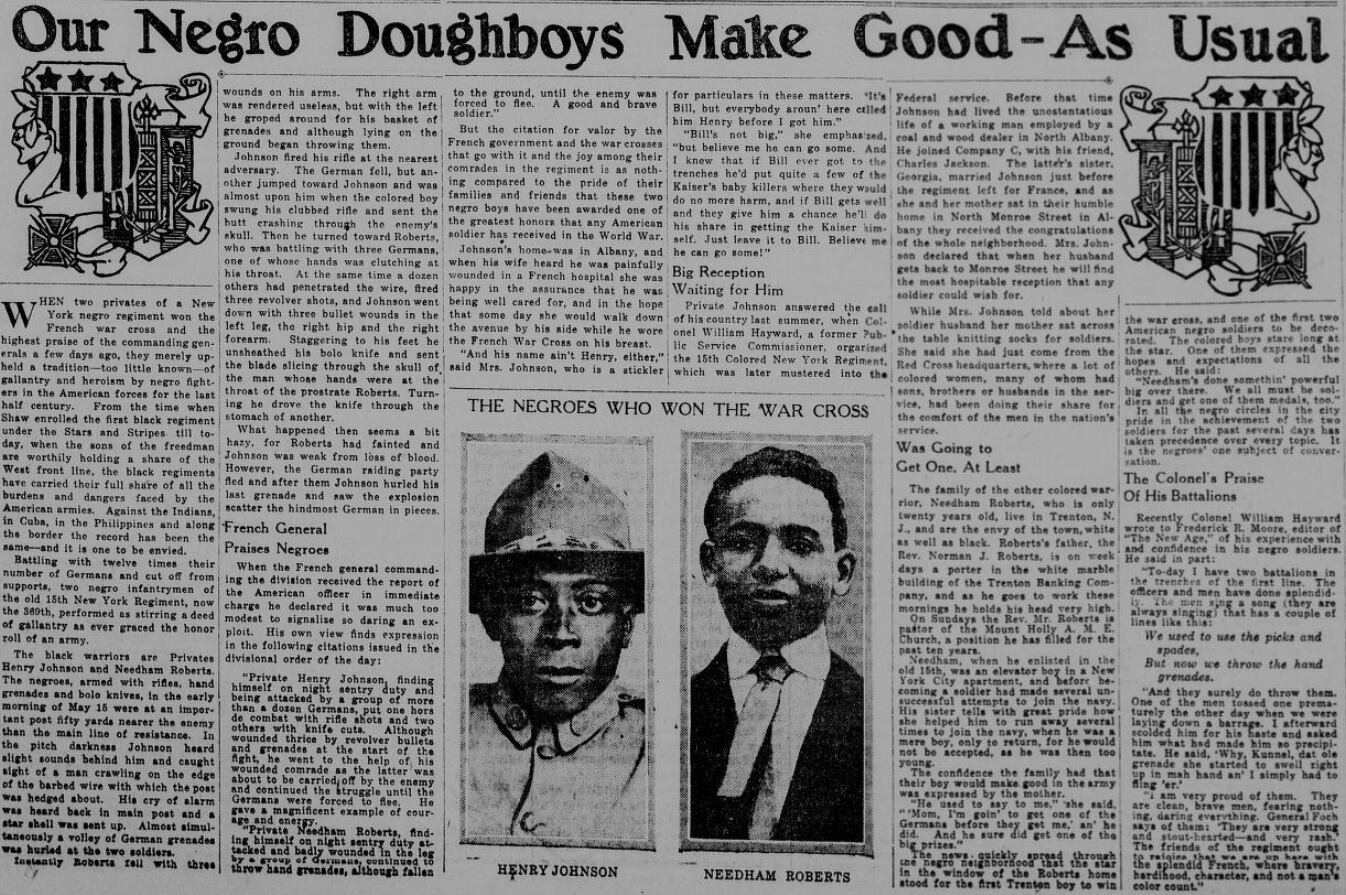

Amid the still of the Argonne Forest during the early morning hours of May 15, 1918, Johnson and 17-year-old Needham Roberts watched and listened, the two sentries ready to raise an alarm that would rouse the reinforcements dozing in trenches and dugouts nearby.

At about 1 a.m., the two men began taking fire from a German sniper. Johnson opened a box of 30 grenades and lined them up for quick use. Moments later, in the terrifying dark of the Western Front, Johnson heard the “snippin’ and clippin’” cutting sounds of at least 12 Germans making their way through the wire encircling the guard post.

Johnson tossed a grenade in the direction of the commotion and all hell broke loose. The German invaders unleashed a wall of gunfire and grenades toward the two watchmen, injuring Needham Roberts immediately.

Unable to walk, Roberts sat upright in the trench and continued to feed Johnson grenades — but the Germans kept coming.

Johnson quickly exhausted the supply and switched to his rifle. It jammed. Enemy soldiers were close enough to touch.

When the Germans attempted to grab Roberts from the trench and take him prisoner, Johnson went to work, abandoning the cover of the trench and swinging his rifle, fists and bolo knife in a tornado of clubbing, punching and cutting.

“Each slash meant something, believe me,” Johnson recalled.

Johnson stabbed one German in the stomach then killed a lieutenant before being shot in the arm. He was then attacked from behind by another, who he discarded by driving his knife into the German’s ribs.

Though increasingly wounded and exhausted, Johnson eventually managed to drag Roberts back to safety just as reinforcements arrived.

The diminutive-yet-Herculean soldier then fainted, fatigued from the melee and the 21 wounds to his arm, feet, face and back — the majority of which were delivered by knives and bayonets. Johnson’s left foot had also been shattered, which he would later have remedied by an inserted steel plate during an operation at a French hospital.

When dawn broke, the Americans found four dead Germans and evidence of at least 10 to 20 more having participated in the attack.

Johnson’s ferocity earned him the nickname “Black Death.” In recognition of his actions, France awarded him with the Croix de Guerre with a Gold Palm for extraordinary valor, making Johnson the first American to receive France’s highest award for bravery. Roberts also received the Croix de Guerre.

The Harlem Hellfighters would go on to spend 191 days fighting in frontline trenches and would sustain 1,500 casualties by war’s end, the most of any single American unit in either category during World War I.

When Johnson returned home to New York, the severity of his injuries prevented him from resuming his pre-war job at Albany’s Union Station. Sadly, Johnson turned to the bottle, became estranged from his family and faded from the memory of those who once celebrated his heroism.

Johnson contracted tuberculosis and later died, destitute, in July 1929 of myocarditis at the age of 36. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

In 2015, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Johnson the Medal of Honor. Henry Johnson was also awarded the Purple Heart and the Distinguished Service Cross in 1996 and 2002, respectively.

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.