“How do we, in the military, encourage our war fighters to be flexible thinkers?” I get asked this a lot — from Quantico to West Point to the Army Futures Forum last December. No matter what military gathering I attend, I keep getting a version of this question.

Our new century requires new levels of creativity to survive, and the armed forces are no exception. In a world where America’s enemies seem to be adapting, evolving and innovating new ways to hurt us, sometimes on a day-to-day basis, those in uniform can’t afford the kind of rigid, linear, textbook mindset that got their predecessors through the Cold War.

Today’s warriors need to be as nimble and imaginative as any tech team in Silicon Valley. But how?

As an outsider looking in, I’ve observed the problem isn’t intellectual, it’s intestinal. I’ve seen more good ideas in any handful of service members than in all the Hollywood executives put together.

The problem is that all those ideas can end a career just as quickly as an enemy round can end a life.

It’s hard for civilians like me to appreciate what being passed over for promotion means. We always have another chance, either in the same job or maybe the next. Hell, in my job, I don’t have to worry too much if my next book fails miserably. I can always write another one.

RELATED

That’s not true when you wear the uniform. I’ve learned enough to understand what a guillotine getting passed over is, and how the internal culture of advancement encourages doing everything possible to avoid that falling blade.

And yet, that same culture is also built on the bedrock of physical courage. It’s not easy to suppress one’s self-preservation instinct. That’s why armies throughout time have awarded individuals who’ve succeeded.

From ancient Rome’s Grass Crown to today’s modern medals, physical decorations tell the world, “I had the courage to risk my life for the lives of others.”

That is why the military needs a new medal — one that recognizes courage under pressure the same way it already recognizes courage under fire.

If service members are awarded for risking their careers (which, let’s face it, mean a lot more to some lifers than their actual, physical lives) then it would go a long way to shedding 20th-century groupthink.

The medal doesn’t have to be official. In fact, some servicemen and women might prefer it not be.

In the 1955 movie “Mister Roberts,” Henry Fonda’s character is awarded the “Order of the Palm” by his men for speaking out on their behalf. In a letter to those men after his transfer, Roberts states, “I’d rather have it than the Congressional Medal of Honor.”

No successful social system works on negative reinforcement alone. Punishment and praise must be equally balanced. If the U.S. military wants the kind of inventiveness we’re seeing from Russia, China and numerous nonstate actors, those inventors need their Order of the Palm.

Of course this medal wouldn’t condone direct insubordination. Even the fictional Mister Roberts respected the chain of command. And of course it wouldn’t be called the “Order of the Palm,” but it could carry the name of a service-specific trailblazer. The “Colonel James Burton Citation” or the “Order of General Billy Mitchell” would go a long way toward unlocking the kind of latent military talent we need to face the threats around us.

And rewarding courage under pressure, not just fire, tells those threats that America will never be outfought, or out-thought.

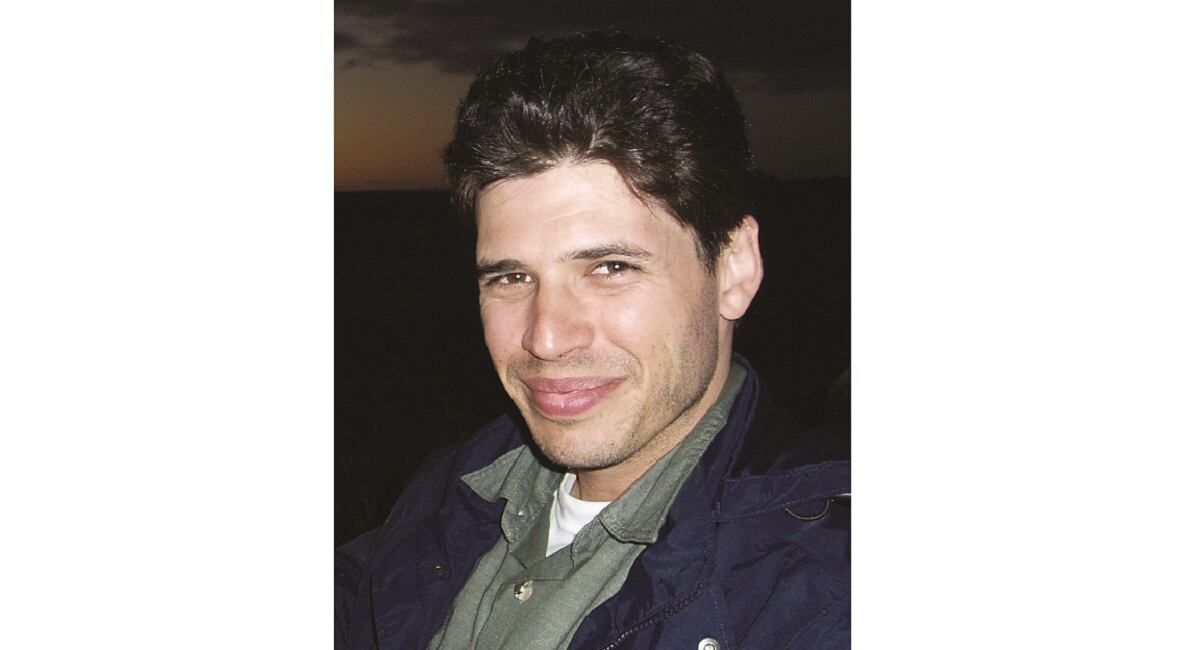

Max Brooks is a nonresident fellow at the Modern War Institute at West Point. He’s the author of “World War Z,” “The Harlem Hellfighters,” The Zombie Survival Guide,“ “Minecraft: The Island” and, coming May 1, “Strategy Strikes Back: How Star Wars Explains Modern Military Conflict.” He’s online at MaxBrooks.com.