When officials signed off Aug. 29 on a Hellfire strike to obliterate a white Toyota they had been monitoring for eight hours, the belief was that it contained ISIS fighters carrying a bomb intended for U.S. troops outside the Kabul airport. The head of U.S. Central Command announced Friday that they were very wrong.

Marine Gen. Frank McKenzie concurred with previous media reports that the strike had killed as many as 10 people, including seven children.

“This strike was taken in the earnest belief that it would prevent an imminent threat to our forces and the evacuees at the airport, but it was a mistake,” he said, confirming that no ISIS fighters are believed to have been killed in the attack.

For days after the strike, Pentagon officials asserted that it had been conducted correctly, despite numerous civilians being killed, including children. The New York Times later raised doubts about that version of events, reporting that the driver of the targeted vehicle was a longtime employee at an American humanitarian organization and citing an absence of evidence to support the Pentagon’s assertion that the vehicle contained explosives.

Army Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters two days after the attack that it appeared to have been a “righteous” strike and that at least one of the people killed was a “facilitator” for the Islamic State group’s Afghanistan affiliate, which had killed 169 Afghan civilians and 13 American service members in a suicide bombing on Aug. 26 at the Kabul airport.

After McKenzie’s remarks, Milley expressed regret.

“This is a horrible tragedy of war and it’s heart wrenching,” Milley told reporters traveling with him in Europe. “We are committed to being fully transparent about this incident.”

“In a dynamic high-threat environment, the commanders on the ground had appropriate authority and had reasonable certainty that the target was valid, but after deeper post-strike analysis our conclusion is that innocent civilians were killed,” Milley added.

Accounts from the family, documents from colleagues seen by The Associated Press, and the scene at the family home — where Zemerai Ahmadi’s car was struck by a Hellfire missile just as he pulled into the driveway — all painted a picture of a family that had worked for Americans and were trying to gain visas to the United States, fearing for their lives under the Taliban.

The family said that when the 37-year-old Zemerai, alone in his car, pulled up to the house, he honked his horn. His 11-year-old son ran out and Zemerai let the boy get in and drive the car into the driveway. The other kids ran out to watch, and the missile incinerated the car, killing seven children and an adult son and nephew of Zemerai.

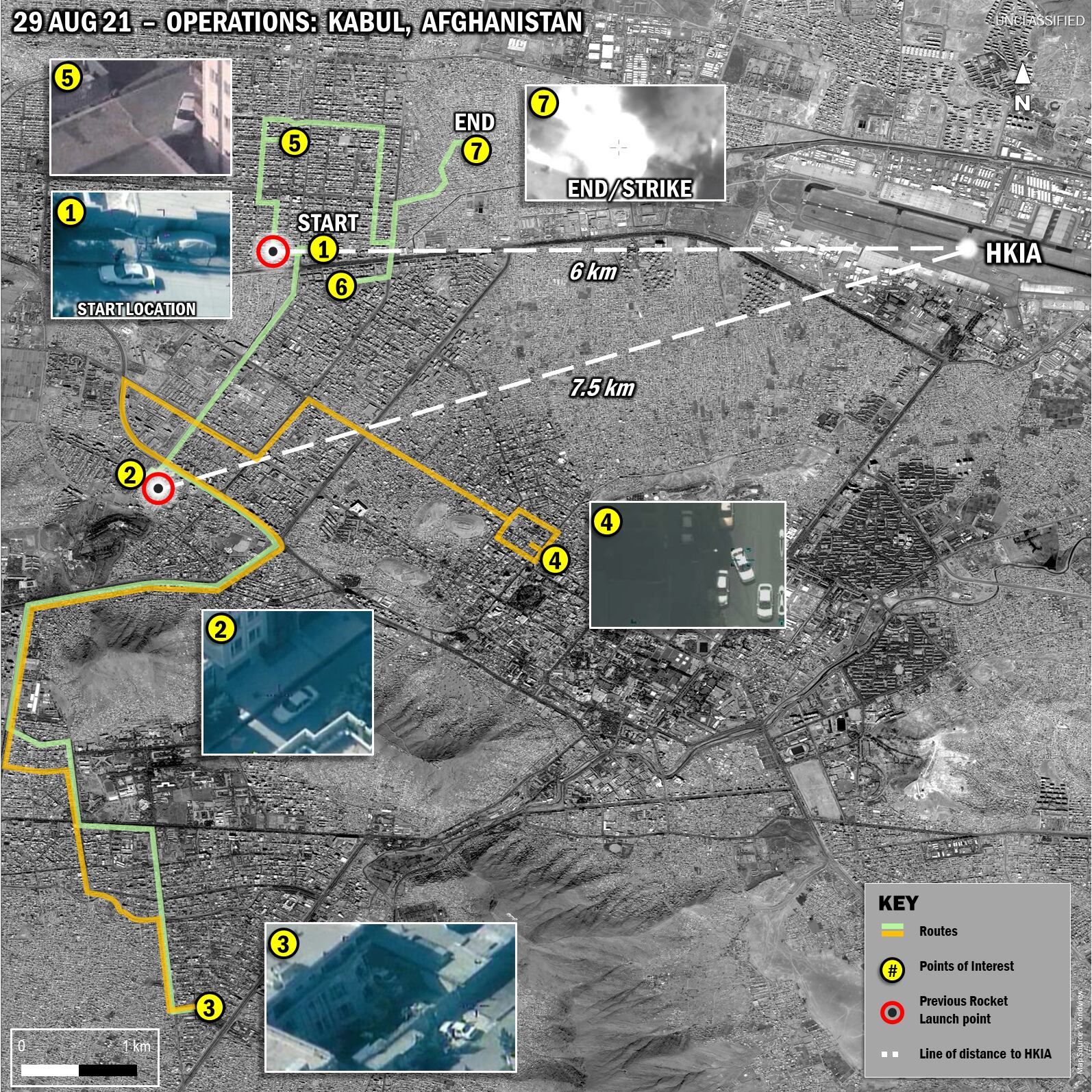

But to officials tracking the Corolla, Zemerai and his vehicle matched intelligence reports of an imminent, ISIS-generated attack against troops at the Kabul airport. At the time, McKenzie said, they were tracking roughly 60 reports of threats.

One of those, specifically, had been a white Toyota. When they saw the vehicle stop outside of a known ISIS compound in the city, then make several more stops, picking up and dropping off several adult men, loading and unloading supplies, they thought they had their target.

“We tracked a lot of other people. We didn’t track anybody ... as closely as we did this, because of limitations on our resources,” McKenzie said. “And frankly, you know, we thought this was a good lead. We were wrong.”

One of those stops was to the office of Nutrition and Education International ― a non-governmental aid organization Zemerai had worked for over the previous 15 years.

Just before 5 p.m., McKenzie said, the vehicle pulled up to a compound approximately 3 km from the airport, prompting concern that if they had the right car, it could be at the airport gate within minutes.

“So the cumulative force of ... the intelligence that we gathered throughout the day, the position of the vehicle, its nearness to the airport, the imminence of the threat, and the other signals that we were getting throughout the day, all led us to the moment of deciding to take the strike,” he said.

Reports in Kabul quickly accused the U.S. of having killed nearly a dozen people, most of them children, but Pentagon leadership held to their original narrative in the following days, despite admitting there was a possibility of civilian collateral casualties.

RELATED

One of their data points was that a secondary explosion after the strike, suggesting that there was explosive material in the car. McKenzie did not completely rule that out Friday, but said “the most likely cause was ignition of gas from a propane tank located immediately behind the car” when it exploded.

Those other imminent threats never materialized, but McKenzie could not say why. He hypothesized that an attack in Nangahar Province two days earlier had killed an ISIS-K planner associated with the potential attack.

The Defense Department is considering death gratuity payments to the families, McKenzie said. There will be some logistical challenges involved, because there are no more U.S. officials on the ground and the country is under total Taliban control.

On that note, McKenzie fielded questions on how CENTCOM’s “over-the-horizon capability” will be able to effectively target ISIS now that on-the-ground intelligence is no longer an option ― especially in light of how wrong this initial strike went.

“That is not the way that we would strike in an OTH mission going into Afghanistan against ISIS key targets,” he said. “For one thing, that will not be a self-defense strike. It will be done ... under different rules of engagement.”

Though McKenzie said the Aug. 29 strike was “not rushed,” he did clarify the difference between how they would go about responding to an imminent threat against U.S. troops versus a highly choreographed attack on ISIS-K assets.

“We will have a lot more opportunity, probably, than we had under this extreme time pressure to take a look at the target ... with multiple platforms, to have an opportunity to develop extended pattern of life,” he said. “None of these things were available to us, given the urgent and pressing nature of the imminent threat to our forces.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.