As court-martial proceedings begin for the Marine behind the wheel in a fatal vehicle rollover that took place outside Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in 2022, he’ll be getting support inside the courtroom from an unlikely source: several of the parents of Marines killed and hurt in the tragedy.

Lance Cpl. Luis Ponce-Barrera, 20, faces charges of manslaughter and reckless operation of a vehicle in the January 2022 rollover of a medium tactical vehicle replacement, or 7-ton truck, that he’d been driving to a landing zone on base.

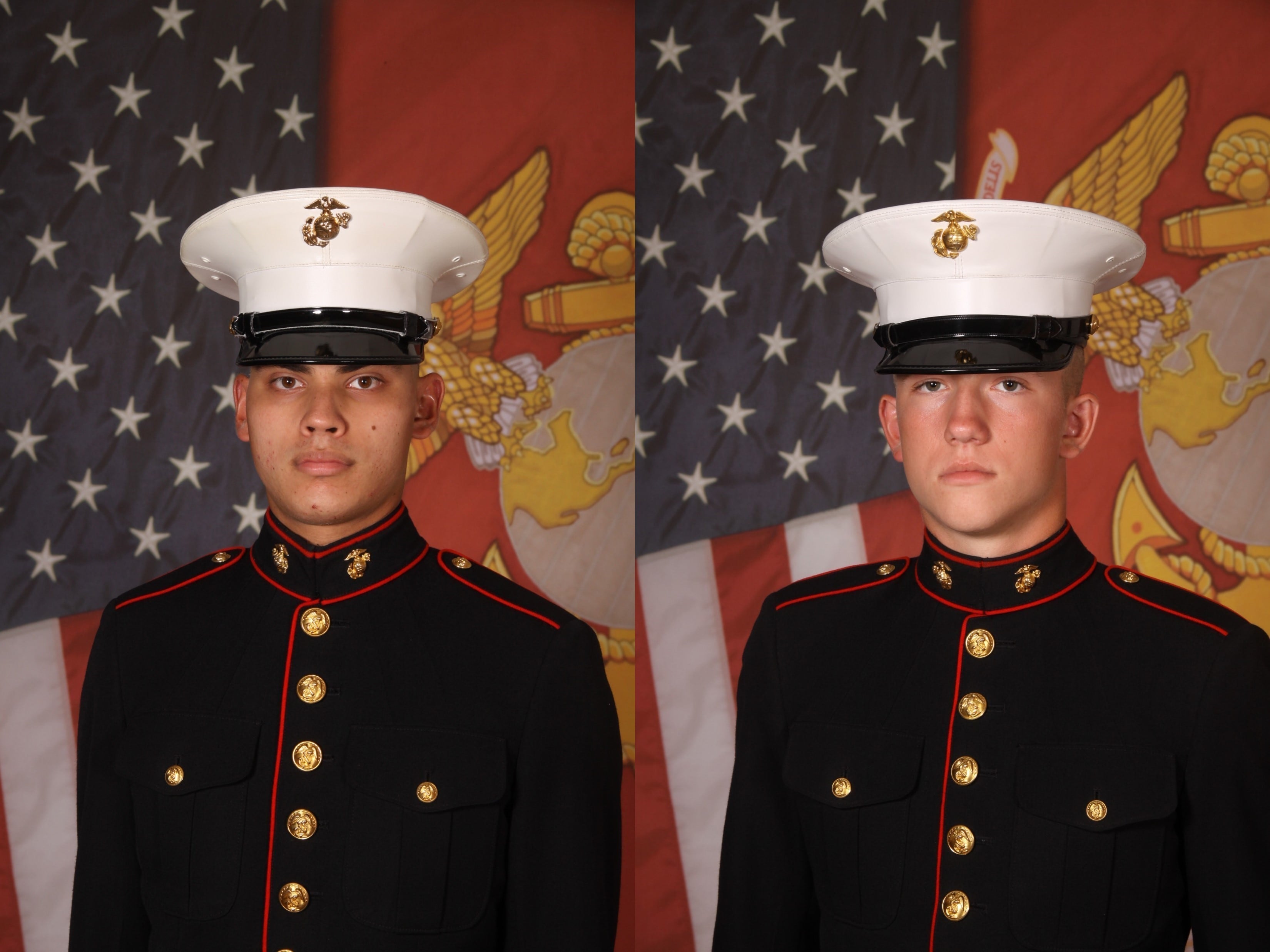

The 19 Marines in the back were ejected. One, 18-year-old Pfc. Zachary Riffle, was fatally crushed by the truck, and another, 19-year-old Lance Cpl. Jonathan Gierke, was hit and killed in the traffic median by a following joint light tactical vehicle that couldn’t stop in time. All the other troops were injured, some critically.

Ponce-Barrera’s trial was set to begin Monday, according to a military docket. But a half-dozen family members of Marines involved in the rollover say they’ve come to believe the junior Marine shouldn’t be held solely accountable for a mishap made possible by lax training standards and a casual approach to risk.

Heading up the campaign for answers and accountability from the Marine Corps are Jen and Rebecca Riffle, Pfc. Riffle’s stepmother and mother.

After compiling a library of documents related to the rollover, and speaking with Ponce-Barrera himself, Jen Riffle said she believes that Ponce-Barrera didn’t have the training he needed to drive the 7-ton, and that the Marine Corps has failed to implement the corrections needed to stop a tragic series of on-duty rollovers. She also said she’s not satisfied with the care the surviving Marines have received following the traumatic incident.

RELATED

“It doesn’t feel like anybody’s looking up the chain of command to see what the hell happened,” Riffle told Marine Corps Times.

In the lead-up to the court-martial, she said, Lt. Gen. David Ottignon, commanding general of Lejeune’s II Marine Expeditionary Force, has declined repeated requests for a meeting, even as he made decisions regarding a prospective plea agreement. And, she said, a detailed series of questions about the circumstances of the incident have gone unanswered.

The command could not respond to specific questions about the rollover in order to preserve the integrity of the trial, a spokeswoman for II Marine Expeditionary Force, 1st Lt. Rebekah Harasick, told Marine Corps Times via email.

“There will likely be more than two dozen witnesses who participate in this case, and Lt. Gen. Ottignon has declined to meet with any potential witnesses in order to avoid creating any actual or perceived bias or personal interest in the cases’ outcome,” she said. “This does not reflect a lack of interest in hearing from Marines’ families.”

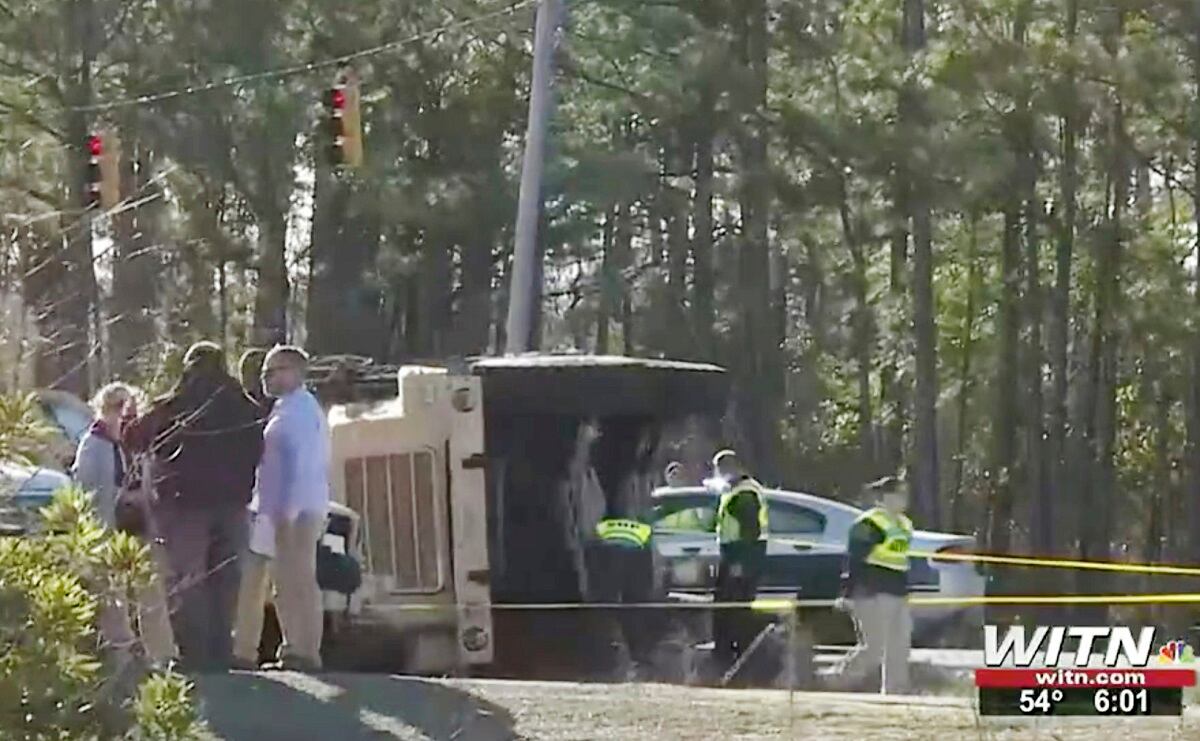

According to a line-of-duty investigation reviewed by Marine Corps Times, Ponce-Barrera was part of a two-vehicle convoy tasked with transporting two dozen Marines from Combat Logistics Battalion 24 to Lejeune’s Landing Zone Condor for helicopter support training around 12:30 p.m. on Jan. 19, 2022.

Approaching the base from its backside, near the small town of Sneads Ferry, North Carolina, the 7-ton was traveling west on North Carolina Highway 210 when it took a turn onto U.S. 17, toward the Landing Zone.

Witness accounts offer different guesses as to how fast Ponce-Barrera was driving: One Marine guessed the truck was traveling at 55 miles per hour; others estimated it made the turn between 30 miles per hour and 40 miles per hour.

At any rate, the turn spelled immediate trouble. The truck’s right rear wheel came off the road, and the vehicle’s bulk and momentum carried it over in a roll to a forceful landing on its right side.

Witnesses say Ponce-Barrera had braked late as the 7-ton approached a red light at the intersection of the two highways. When the light turned green, they said, he panicked, hitting the gas and taking the sudden turn far too hard. All the truck’s passengers were ejected as the truck shuddered into the median on its side.

Some vehicle passengers who gave statements said they’d observed Ponce-Barrera accelerating too much and braking too hard at multiple points on the 30-minute journey, despite the fact the Marines had plenty of time to reach their destination.

For Jen Riffle, that’s all beside the point.

In February, after months of efforts to make contact, she said she and other family members had a Zoom meeting with Ponce-Barrera, facilitated by his military defense attorney, Capt. Brentt McGee.

A child of immigrants, Ponce-Barrera told her, she said, that he had had 20 total hours of experience driving heavy military vehicles, and that he’d never driven a 7-ton with a turret on top until that day. He wasn’t even supposed to drive that day, she said; he was tapped at the last minute to fill in for another Marine.

“He talked about, you know, trying to get the feel of the brakes and gas and everything,” she said. “It just makes me think of a newer driver.”

The 2020 Marine Corps order that lays out licensure requirements for tactical motor transport vehicles does not specify the minimum number of driving hours required, it emphasizes the responsibility of leaders to ensure drivers are ready.

“Successful licensing of an applicant does not signify the operator is capable or prepared to operate a vehicle in every situation or environment,” it states. “It is every commander’s responsibility to continue to build upon these basic skills through implementation of an operator development, skill progression and sustainment training program.”

Riffle couldn’t help feeling that Ponce-Barrera was set up to fail. And when he asked, at the end of the two-hour call, if she’d sit beside him on the defense side, she didn’t have to think about it long.

“It’s one of those things where we feel like it’s the right thing to do,” she said. “Hopefully, that’ll speak volumes without saying anything.”

William Gierke, Jonathan Gierke’s father, also planned to be in the courtroom. His feelings about the trial are mixed, but he does believe accountability should stretch farther than it appears to in this case.

“Ultimately, I guess they should go further up the chain of command, and find out who was the instructor, who were the ones involved in his training, you know?” he said of Ponce-Barrera. “Was he just newly licensed and they said, here’s a seven-ton vehicle you’ve gotta drive with 17 people in the back?”

The father of another Marine who’d been Zach Riffle’s roommate, and who sustained a traumatic brain injury in the rollover, said he didn’t feel the highway transport of 17 Marines was an appropriate tasker for a then-teenage lance corporal fresh out of training.

The Corps’ handling of the tragedy, he said, “put a bad taste in my mouth.” He spoke anonymously to avoid repercussions for his son, who is likely to testify in the trial.

‘I know. And I’m willing.”

The families in this case are just the latest to call for meaningful change following a deadly series of vehicle rollovers in the Army and Marine Corps.

A 2021 Government Accountability Office report found 123 troops had died in noncombat tactical vehicle incidents between 2010–2019, and that “driver inattention, supervision lapses and training shortfalls were common causes.”

For the Marine Corps, the report recommended establishment of better-defined roles for vehicle commanders and procedures for risk management; ensuring full staffing of personnel responsible for vehicle safety; defining specific performance standards and criteria to assess driver skills; and verifying that leaders are communicating to units about topography hazards at ranges and training locations.

Marine Corps leadership concurred with all the findings, and submitted an action plan in November 2022 detailing how they planned to address them. But the Government Accountability Office still lists them all as “open,” meaning that satisfactory action has not been taken.

RELATED

In recent years, the charge for reform in tactical vehicle training and supervision has been led by Michael McDowell, a fellow in New America’s International Security Program whose son, 1st Lt. Conor McDowell, was killed in a May 2019 light armored vehicle rollover at Camp Pendleton, California.

McDowell ultimately was determined not at fault in the accident. In 2022, Michael McDowell was behind a successful push to create a pilot program that would install “black box” data recorders on a number of tactical vehicles to assess their operation.

“How come this is happening?” McDowell said of the unexpected phenomenon of victims’ families standing, to varying extents, in support of the mishap vehicle’s driver. “Well, it’s part of a pattern. It’s blame down, not blame up, and we need to blame up. Because these generals are public servants and public officials.”

Ponce-Barrera’s court-martial is currently docketed to run from Monday through April 14, though that timeline may shift.

Regardless of the outcome of trial, the families who lost Marines or continue to help them recover from serious injuries understand their losses can never be made whole.

Rebecca Riffle, Zach Riffle’s mother, remembers her son’s winning smile and how he excelled at everything he tried. He gave up his senior year of competitive wrestling, she said, to enlist in the Marine Corps.

“And I said, ‘Zach, you understand that by joining, that you were writing a blank check to your country, payable up to and including your life? And he said, ‘Yes, Mom, I know. And I’m willing.’”

Hope Hodge Seck is an award-winning investigative and enterprise reporter covering the U.S. military and national defense. The former managing editor of Military.com, her work has also appeared in the Washington Post, Politico Magazine, USA Today and Popular Mechanics.